Dear Sports Fan,

How does kneeling work in football? This is one part of the game that I just don’t understand. Even in a close game, it seems like both teams decide that the game is over while there is still time on the clock. Why is that? And when does it happen?

Thanks,

Jack

Dear Jack,

Football is the ultimate effort sport. It’s a cliche that football players and coaches talk about “going 110%” and “leaving it all out on the field.” To which most people reply, “you can’t go harder than 100%, that’s nonsensical” and as for “leaving it all out on the field, we hope that doesn’t include your pants, underwear, or long-term health.” Nonetheless, it does seem like football players and coaches constantly give their full effort to winning the game. That makes it all the more disconcerting for viewers when the game ends with one or a series of plays where neither team seems to be trying at all. These plays are called kneel downs or quarterback kneels. The quarterback kneel is sort of like what happens in a chess game when one player sees that their opponent will be able to checkmate them in a few moves, no matter what they do. It’s a concession, but in this case the initiative is taken by the winning side instead of the losing side. When a team kneels, they’re saying that they are willing to sacrifice their attempt to advance the ball in order to safely run time off the clock. Here’s how it works.

Football is a game with a clock. In each quarter of the game, the clock starts at fifteen minutes (for this post, we’re assuming that you’re watching the NFL, but things are almost the same in college football) in each quarter and counts down to zero. When the clock hits zero in the fourth quarter, the game is over and whichever team has more points, wins. It’s also a game of alternating possessions. One team has the ball and keeps it as long as they can move the ball ten yards in four plays (if this concept is still blurry for you, read our post on down and distance). Although most plays last for only a few seconds to a dozen, the clock may count down between plays. Whether or not the clock runs is based on the outcome of the previous play. The rules that dictate this are somewhat Byzantine but to understand the kneel down, you only need to know that if a player who has the ball is tackled within the field, the clock runs between plays. When a player (usually the quarterback) kneels with the ball, they are performing a ritual equivalent of being tackled with the ball — instead of actually being tackled, according to NFL rules, they are allowed to simulate being tackled by voluntarily kneeling. When a quarterback kneels with the ball, that play is over and the ball is set up for the next play. Teams are allowed up to forty seconds between plays. So, a team that kneels the ball can expect that action to allow around 42 seconds to run off the clock. The reason why it’s 42 and not 40 is that the play itself might take around three seconds and a team will snap the ball with about one second left on the forty-second play clock.

Like so much of football, the simple concept of kneeling is complicated by a few technicalities. If you enjoy technicalities, you’ll love football! There’s a reason why so many NFL referees are lawyers! The first technicality is that the clock always stops on a change of possession. A change of possession, when the team that starts with the ball on one play does not start with the ball on the next is normally the result of an interception, a fumble, or a punt but it can also be the result of a fourth down play that isn’t a punt but doesn’t result in a first down. In other words, if a team kneels on fourth down, the game clock will immediately stop at the end of the play; it will not run once the play is done. That effectively limits kneeling to be a first, second, or third down tactic. The other technicality is that each team gets three timeouts per half. These timeouts can be used between any two plays and they result, not only in a commercial break, but also in the game clock stopping between plays. A time out can counteract the effect of kneeling. The last technicality is the two-minute warning. This is an arbitrary timeout that’s called (but not charged to either team) after the last play that starts before the game clock has hit 2:00 remaining in the second and fourth quarters. The two-minute warning would also stop the clock between plays, so kneeling before it is rare.

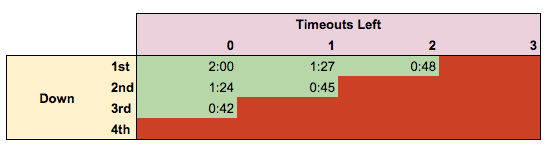

So, how do you know when a team is going to use the kneeling strategy? Usually, a team will only kneel if, by kneeling on successive plays, they can run the clock all the way to zero and therefore conclusively win the game. The exact time in a game when they can do this is modified by the number of timeouts the team without the ball has and the down for the team that has the ball and is leading the game. It’s a sliding scale best expressed as a table:

Remember, a team can waste 42 seconds per kneel down but that is made up of three seconds to execute the kneel and another 39 that runs off between plays if the clock does not stop. Here’s a few examples of how I got to the numbers in the cells:

- 1st down, one timeout remaining: 1st down — kneel for three seconds, defense takes a timeout; 2nd down — kneel for three seconds (6 total), defense has no timeouts remaining, so the clock runs an additional 39 seconds (45 total); 3rd down — kneel for three seconds (48 total), defense has no time remaining, so the clock runs an additional 39 seconds (87 or 1:27 total).

- 2nd down, no timeouts remaining: 2nd down, kneel for three seconds, clock runs an additional 39 (42 total); third down — kneel for three seconds, clock runs an additional 39 (84 or 1:24 total).

You can see from this chart how the two-minute warning affects this strategy by effectively giving the trailing team another timeout. If it weren’t for that official timeout at 2:00, the top left cell would read 2:06 and teams would be able to safely start kneeling six seconds earlier than they do now.

The tactic of kneeling in football is a bit of a strange cultural fit. It’s odd to see teams that have tried so hard and so violently to beat each other, go through the motions of the final plays in the game. Allowing the offense to mimic being tackled in order to run the clock down isn’t a fair representation of a normal football play because it takes away the ability of the defense to create a fumble or interception and get the ball back immediately for their team. Nonetheless, it’s the way things are done today by rule and by custom. At least now I hope you understand what it is and how it works.

Thanks for the question,

Ezra Fischer