Dear Sports Fan,

What’s the plot of this year’s Super Bowl? I’m going to my friends’ Super Bowl party and I think it will be more fun watching the game if I know what to watch for.

Thanks,

Lucie

Dear Lucie,

Thanks again for your question. This is part two of a three part answer to it. At Dear Sports Fan, we believe that following sports like soap opera is the most enjoyable way to be a sports fan. If you missed part one and part two, I’d love for you to read them, but you don’t need to to understand this one!

What positions matter?

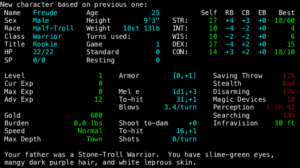

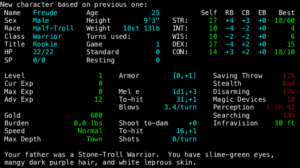

Recently I starting playing a role-playing computer game from 1990 that I loved as a kid called Angband. Like many games of its type, when you begin creating a new character, you need to decide where to distribute points across a number of qualities, in this case: strength, intelligence, wisdom, dexterity, and constitution. It’s a zero sum game. Each point you give to strength is one you can’t give to dexterity or wisdom.

Building a football team is a lot like creating a character in a role playing game. Thanks to the NFL’s salary cap rules, each team has a limited amount of money they can spend on player salaries. Each dollar you devote to one position, is a dollar you cannot spend on another. You have to choose what positions you think are most important to invest in.

In every era of the NFL, there are certain consensus about what positions are most important to invest in. The Blind Side, by Michael Lewis is, essentially, the story of a shift in this consensus, from thinking that every position on the offensive line was similar and not worthy of investment, to the belief that the left tackle was the most important and worthy of incredible investment.

The NFL today is in the middle of another shift in positional valuations and this Super Bowl is set up perfectly to provide a referendum on the current trends because when it comes to which positions the Patriots invest in, they mostly conform with the current trends while the Rams buck the trends in several important ways. If this narrative (which I think I made up this morning) is true, then it’s important not only to General Managers throughout the league but also to players whose ability to get hired and paid might hinge on the outcome of the game.

The current trends in the NFL suggest a few things:

Offense rules supreme over defense

In the ongoing football conflict between offense and defense, offense has been winning for a while, but this year felt like the year the entire concept of defense broke/transformed.

For the basically the whole history of the NFL, defenses have been trying to shut down offenses entirely and the most elite, best defenses in the league had a good shot at demoralizing an offense. Thanks to a series of rule changes that favor offense and an explosion of creative offensive ideas, in 2018, defenses don’t really have a fair shot at being an overpowering force. In 2018, the best defenses in the league still gave up an average of over 17 points — two touchdowns and a field goal. Like all reasonably entities when faced with a losing cause, teams have shifted their expectations for their defense. Instead of winning through defense teams hope their defenses just don’t totally lose the game for them.

So, you’d expect that winning teams would spend a larger proportion of their money on offensive players. The Patriots are reasonably on trend when it comes to this: their overall split is 46% on offense and 40% on defense (the other 4% is on special teams). The Rams, on the other hand, go against trend and spend 50% on defense and only 34% on offense.

This slant is most clearly seen on the Rams defensive line where they have committed a whopping $42 million, by far the most of any positional group. By comparison, the Patriots have committed only $17 million to their defensive line.

The Rams love defensive linemen. They signed their best defense lineman, Aaron Donald before the year to the “richest deal in NFL history” but because that doesn’t go into affect until next season, he’s not even the highest paid defensive lineman on the team. (That would be famous friend of Warren Buffet, Ndamukong Suh.) They even doubled down (I hate that phrase, but it’s fitting here) on their commitment during the year by trading for Dante Fowler, another highly paid/regarded defensive lineman.

This might seem like a smart strategy, given the old truism about beating Tom Brady in the Super Bowl: that you need to pressure him without blitzing — only possible with an excellent defensive line. But note that it’s an old truism that relies on the Super Bowls from 2008 and 2012 as evidence. When the Patriots lost in the Super Bowl last year, it had nothing to do with the opposing team’s defense — they were terrible but the Patriots own defense was even worse.

Running backs are essentially interchangeable and not worth paying for.

Teams in today’s NFL are consistently featuring young running backs who are on their rookie contracts (The initial contract a player gets as a rookie covers four or five years and is pegged to his draft position. Unless a player is a bust and way worse than projected, rookie contracts are almost always less than what the player would make on their next contract.) There’s an open debate about whether even the very best running back is worth investing a lot of money into. Perhaps the best running back in the league, Le’Veon Bell, sat out the entire year this year because his team would not commit to paying him what he thought they should.

The Patriots conform reasonably well to this trend despite utilizing running backs more than almost any other team in the league. They have three running backs: James White, Sony Michele, and Rex Burkhead and they use all of them throughout the game. These three combined make about as much money as the Rams starting running back, Todd Gurley, who, before the year began, signed the highest ever contract for a running back. By signing Gurley to a four year, $60 million dollar contract, the Rams firmly took a contrarian stand against the trend of devaluing the running back position.

Gurley is undeniably a phenomenal running back and a star in the league. He led the NFL in all sorts of running stats this season and, perhaps more importantly, was seen as the driving force behind the Rams offense. The Rams are most effective throwing the ball when they use what is called a play action pass or a fake run. So you could argue that Gurley’s strength as a runner, even if it’s not important in itself, is vital because it forces defenses to respect the fake-run passing plays. So maybe the Rams’ bucking of the trend against paying running backs will prove to be worth it.

—

What makes a football team great? Who should you pay the most? Where should a team splurge and where should it skimp? The result of this year’s super bowl will validate current trends in answering these questions and possibly even start some new ones.