One of the great things about watching sports is that they are multi-layered entertainment. The most casual fan can turn on a game and immediately enjoy the beauty of watching incredibly fit people do insanely graceful things with their bodies. Someone who doesn’t know anything about a sport but loves competition will find it easy to get engaged in a close game. A moderate fan starts to learn some of the characters in the drama – the players and coaches whose personalities influence the outcome of the game and how fans feel about it. An intermediate fan will learn about the many technicalities of the game, from rules to basic tactics. A serious fan of a sport or team will become an expert in history, know the background and personalities of all the players, and has a deep intellectual and instinctual understanding of how the game works from tactics to rules to strategies. Each sport has its own ladder of learning, something which we try to unravel on Dear Sports Fan. No matter how long you’re involved with a sport, however, there always seems to be another layer of the onion to peel; something else that remains unknown – something else to learn. In basketball, the very pinnacle of understanding, the single thing which remains unknowable to virtually all fans and even most players and coaches is the triangle offense.

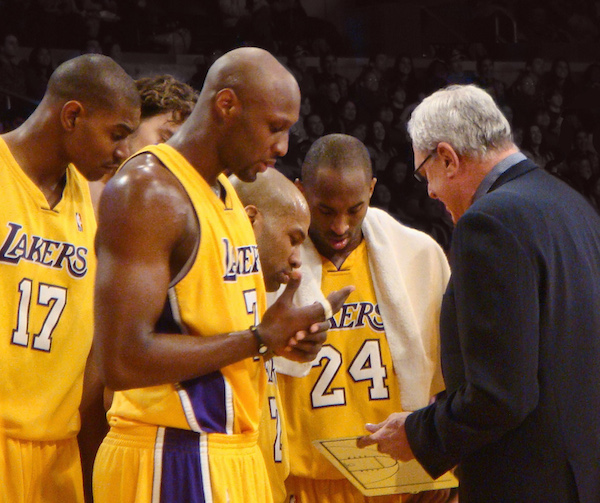

Although it’s much less obvious, basketball teams, like football teams, have distinct offensive plays and strategies which vary from team to team. Although most offenses share similar concepts, like the pick and roll, each one is its own unique animal. In this animal kingdom of offensive strategies, the triangle offense is the panther – complex, mysterious, and totally dominant. The most winning teams of the past 20+ years of basketball history, the Chicago Bulls of the 1990s (six championships) and the Los Angeles Lakers of the 2000s (five championships) have used the triangle offense. Despite all that notoriety, the offense has remained literally invisible to casual fans and totally inscrutable to virtually everyone else. Without being able to understand how it works, people have taken to debating its existence. Is the triangle offense really what drove those teams to their success or is it a “MacGuffin” — a meaningless sleight of hand created by Phil Jackson, coach of both teams, to distract competitors and commentators from whatever his true strategy was?

In a truly brilliant New York Times article, “The Obtuse Triangle,” Nicholas Dawidoff, set out to discover, once and for all, the essential nature of the triangle offense, the unorthodox thinker, Tex Winter, who created it, and the enigmatic coach, Phil Jackson, who used it to such success. Here are some of my favorite selections from the story, but you should read it all. It’s bright and accessible to even the most casual basketball fan.

Dawidoff discovers that, as opposed to other offenses that are an accumulation of set plays, the triangle offense is a philosophy of interpretation that must be shared by all five players on the court inorder to be effective:

Winter empowers his players to read the defense and make situational decisions within the flow of the game, so the tricky part is that everyone must recognize the same opportunity and choose the same response. In effect, Winter wants five basketball Peyton Mannings on the floor, scanning the defense, deciphering its intentions, flashing around the court in well-spaced concert, exploiting vulnerability.

Part of Dawidoff’s investigative process was reading a book Winter wrote and published which detailed the triangle offense for all to read. Offenses are usually tightly guarded secrets, but as you’ll see in a minute, Winter felt comfortable sharing his for one very good reason:

When a Baltimore Bullets scout named Jerry Krause visited Kansas State, Winter gave Krause his book to read. Krause complimented the book, and Winter mentioned that he had sent copies to his rival coaches in the Big 8 Conference.

“I said, ‘Why are you giving away your secrets?’ ” Krause said. “He said: ‘I’m not. It’ll only confuse them.’ ”

Triangle deniers often point out that Jackson’s championship teams had first Michael Jordan and then Kobe Bryant and Shaquille O’Neill on them. That’s three of the top ten players in the past 40 years. A big part of the article grapples with this question. The eventual conclusion seems to be that while no offense can succeed without great players, great players also can’t succeed (at least as consistently and frequently as Jordan, O’Neill, and Bryant did) without a great system.

Jackson and Winter’s thinking was that if they built more offensive options around him, Jordan would have greater reserves of energy at the end of playoff games. They told Jordan that for 20 seconds, the team would stay in the offense. If no clear scoring opportunities emerged, then he should create one. Jordan was skeptical; he called the triangle “a white man’s offense.”

Jordan’s teammate Horace Grant describes the give-and-take between crediting the offense and the star players:

“It was a smooth operating machine. Baryshnikov in action! Picasso painting! A beautiful thing! Having Michael Jordan and Scottie Pippen helped, too. Shot clock’s at four, it all breaks down, then Jordan time.”