Dear Sports Fan,

What is a force play in baseball or softball? I’m new to watching and it seems like force is an important concept but I’ve yet to here a good explanation. Can you help?

Thanks,

Caroline

Dear Caroline,

The force play is one of the most integral concepts in baseball and softball. Without an understanding of it, not much in the game will make sense. Unfortunately, because most baseball broadcasts assume that all of their viewers grew up playing or watching baseball or softball, there aren’t commonly explanations of what a force play is or what its implications are. A force play is a kind of short-hand; a convenience that the defense or fielding team gets to use against the team that’s trying to score. In some situations, instead of having to tag the opposing player with the ball to make an out, a defensive player with the ball can step on a base and immediately create an out. The reason for this convenience is predicated on a single concept – two base runners can never occupy the same base at the same time.

How do we make the leap from two players not being able to be on the same base at the same time to being able to get someone out just by stepping on a base? Let’s run through a scenario where there is no force play available to the defense. Imagine that there is a base runner on second base but not first or third. When the player that is batting hits the ball into the field, he has to run to first. The player on second can either stay on second base or run to third. He starts running and then sees that the opposing team has a chance to throw the ball to third before he can get there. If he keeps running, he’s likely to get tagged by the player with the ball before he can make it safely to third. So, he turns around and runs back to second base. If he can make it back there without being tagged, he’s safe. He has options – second or third base. Either one is a safe haven. There is no possible force out.

Now we’ll take a similar scenario but add in a force play. Imagine everything were the same except that instead of having only a runner on second base, there was also a runner on first base when the batter hit the ball. The batter still has to run to first base. But wait! There’s a runner already there. If he stays put, there will be two runners on first base — and we know that’s not allowed. So, the runner on first base has to run to second. Now our runner on second base faces the same dilemma. He has to run to third or else he and his teammate who started the play on first base will both be occupying the same base. So, he starts running to third. The fielding team makes the same play and throws the ball to the defender on third base. The guy running from second to third sees that he’s in trouble but unlike in our first scenario, he can’t turn around and run back to second base. He has teammates already on first and second base, so he can’t run backwards. He has to run forward.

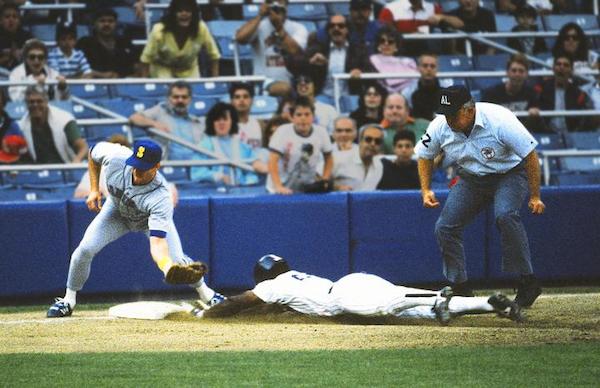

In an imaginary baseball world without the force play rule, the defender standing on third base with the baseball would wait for the runner to get to him and then step forward to tag him with the ball. This would work close to 100% of the time because the runner has no options other than to run straight into the defender. In effect, the outcome of the play is set by the time the defender gets the ball on third base. The out is fait accompli. Instead of waiting for the inevitable, baseball created the force out rule. If a runner has no option but to run forward to a base, and a defender can get to that base with the ball before the runner does, it’s immediately an out.

This seemingly small convenience has widespread tactical consequences. The double-play, one of the most exciting plays in baseball, when the defense records two outs on a single hit, would be drastically less possible without the force out. The most common double play, one where there is a runner on first when the batter hits the ball and the defense is able to get the ball to second base, step on it, and then throw the ball to first base before the guy who hit the ball can get there, relies entirely on force plays or outs. If the defense had to wait for the runner on first to get to second before being able to get him out, they’d never have enough time to throw the ball to first before the batter got there.

Here are the two scenarios we described above:

Scenario 1: Home plate [•] First base [ ] Second base [•] Third base [ ]

Scenario 2: Home plate [•] First base [•] Second base [•] Third base [ ]

Can you figure out where the force plays are in these other scenarios?

Scenario 3: Home plate [•] First base [ ] Second base [ ] Third base [•]

Scenario 4: Home plate [•] First base [•] Second base [ ] Third base [•]

Scenario 5: Home plate [•] First base [•] Second base [•] Third base [•]

If you answered – first base for scenario three, third base for scenario four, and first, second, and third base and home plate for scenario five, you’re well on your way to being a baseball and softball force play expert! Here are two bonus facts you might also have picked up on. First base is always a force out. It’s not intuitive because there are no runners moving behind the batter, but nonetheless, once he hits the ball, he has to move to first base. He cannot simply stay at home plate and try again next time. The other bonus fact is a pretty advanced tactical one. In terms of force outs, it’s sometimes better defensively to have more players on base. Referring again to our first two scenarios, the defense may not have been able to get anyone out in the first one, but definitely would have been able to in the second. This goes against what seems to be the normal logic of playing defense in baseball — you want fewer people on base not more. In some situations, teams will intentionally walk a batter to get more runners on base so that they create more force play opportunities during the next at bat.

Thanks for your question,

Ezra Fischer