To celebrate and prepare for the World Cup in Brazil, Dear Sports Fan is publishing a set of posts explaining elements of soccer. We hope you enjoy posts like Why do People Like Soccer? How Does the World Cup Work? Why Do Soccer Players Dive so Much? What is a Penalty Kick in Soccer? and What are Red and Yellow Cards in Soccer? The 2014 World Cup in Brazil begins on June 12 and ends on July 13. Today we have the special treat of a guest post about World Cup soccer balls by an early adopter of Dear Sports Fan, Al Murray. Enjoy!

— — —

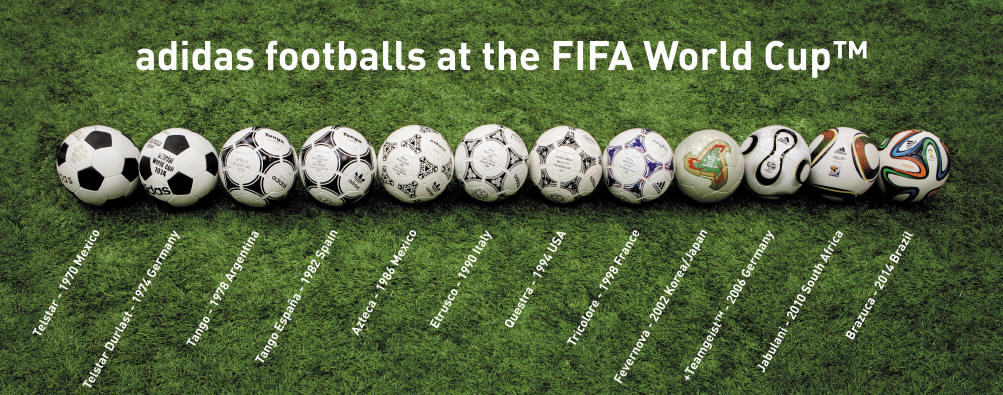

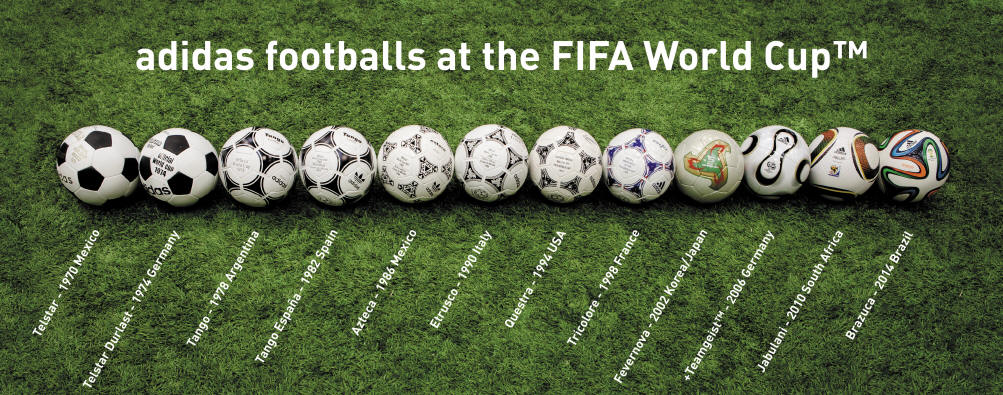

International football players, like most any athlete, praise their own skill when things go right and blame the tools when they go wrong. The last few World Cups have continued this tradition with the introduction of some high-tech balls. Each demonstrated the Law of Unintended Consequences in their own unique way.

In 2006, it was that the Teimgeist, German for “Team Spirit”, ball had too much lift and soared over the goal. It was designed to be smooth to reduce drag, but that meant the ball didn’t react well to the wind and it lifted more than anyone wanted. Interestingly it didn’t curve especially well, but its low drag kept it in the realm of higher velocity for long portions of its flight.

In 2010, it was that the Jo’bulanmi, “To Celebrate” in isiZulu, ball “knuckled” at normal kicking speeds thus making goal tending more difficult. It was designed with special panels to induce better roundness and reduce the sailing of the 2006 ball. While it curved fairly well at both high and lower kicking speeds, the seams caught the air at 45-60 MPH (normal free kick speeds) and caused it to not spin but rather “knuckle” at high speeds. For reference, a traditional soccer ball knuckles at~30 MPH, much slower than anyone kicks.

NASA used the 2010 World Cup as a opportunity to engage students in aerodynamics and posted several studies on soccer balls in flight including a nifty simulator: https://www.grc.nasa.gov/www/k-12/airplane/soccer.html

And for you more mathematically inclined: https://www.grc.nasa.gov/www/k-12/airplane/flteqs.html

There is a really good explanation, with minimal math, at http://www.soccerballworld.com/Physics.htm#world-11-6-8-3

Basically it boils down to this:

- When you kick a ball, it is given velocity and spin.

- At a given spin rate, low velocities/high drag result in high curve rates while high velocities/low drag result in longer flight.

- At a given velocity, higher spin rates impart more curving.

- A good kicker will use both velocity and spin to control the ball.

How a kick works:

- A kick is taken with initial high spin and a velocity (speed & direction) of 45-60, in some cases >70 mph.

- With high velocity the airflow is turbulent, the velocity effect is stronger than the spin, and the ball has low drag and flies high.

- Eventually the velocity drops, as drag effects increase, the air flow becomes more laminar and the spin induces a Magnum force which causes the ball to curve in the direction of the spin usually as it reaches and then comes down from the apex of flight.

- As the ball’s velocity decrease, assuming the rotation speed stays the same, the ball curves more confounding goal keepers (and the occasional outfielder) the world over.

A Good free kicker can shoot the ball outside the defender wall and have it bend back on the goal, sometimes as much as 3 meters! You can see this in long fly balls in baseball and in both free and corner kicks in soccer. Brazilian left fullback and part-time wizard, Roberto Carlos, demonstrates in this video: http://youtu.be/3ECoR__tJNQ?t=1m20s

For 2014, the ball will be the Brazoca, “Brazilian or The Brazilian Way of Life” in Portuguese. I understand they’ve redesigned the ball, getting rid of the flat panels, adding dimples for reduced drag like a golf ball and faster travel with “propeller” patches to add more spin and greater curve at lower speeds. Will this mean more curves? More diving action? More Lift? Or perhaps, given the Law of Unintended Consequences, something completely different?

Guest Author – Al Murray

Interesting! Thanks for the lesson.

Interesting! Thanks for the lesson.