One of the biggest National Football Leagues (NFL) stories in the weeks leading up to the start of the season has been Michael Sam, the first openly gay man to be drafted by a professional team. As interesting as this story has the potential to be, most of the coverage just misses the mark because it fails to establish enough context. Almost all of the stories that I’ve read have assumed a base of knowledge about the offseason process in the NFL that only hardcore NFL fans have. Furthermore, even most attentive sports fans don’t have a real understanding of what the experience and expectations are for a marginal NFL prospect. Without this context, it’s very difficult to tell how much of what Michael Sam is going through is unique because of his historic status and how much of it is completely normal. We simply don’t often pay this much attention to low draft picks or undrafted players in the NFL. In this post, I’ll do my best to explain the context so that we all have a chance of better understanding Michael Sam’s NFL experience. In this effort, I’m aided enormously by Charles Siebert‘s amazing New York Times Magazine profile called The Hard Life of an NFL Long Shot about his nephew, Pat Schiller, who was, in 2012, in a similar situation to Sam’s.

How does the NFL offseason work?

The NFL offseason begins the day after the Super Bowl and ends when the first game of the season is played. It’s a seven month affair. To understand Sam’s experience, we should start at the NFL draft in mid-May. Over the course of a few days, the thirty-two NFL teams select 256 college players, an average of eight players per team although some teams may have more picks, some fewer. The Rams this year had eleven picks. After the draft, the draft picks agents negotiate with the team and most eventually settle on terms and sign a contract. Next up are OTAs or “organized team activities” which are basically glorified practice sessions in June or July that serve as the players first introduction to their teammates and coaches.

The official pre-season consists of four games exhibition games in consecutive weekends starting on August 7th this year. These four weeks of pre-season football work like a giant audition that teams hold for players. Strict rules and dates apply to this process. For the first three games, teams are allowed to have 90 people on their rosters. After the third game, teams have to cut their players/applicants down from 90 to 75. After the fourth game, that number drops to the regular season norm, 53 players per team. In the course of a month, the number of players on NFL teams goes from 2,880 to 1,696 for a reduction of 41%. In a lot of ways, this whole process reminds me of the job market for professors. Each year hundreds of new PhDs come out of graduate school but the number of professor jobs remains relatively static. So it is with football players. Each year, around 300 college players try to get jobs in the NFL but the number of available jobs remain the same. There’s simply not enough room for everyone.

Football is a brutal game on the field and a brutal business off it. Players who get cut get nothing — contracts at this level have no guaranteed money. Their options are bleak because there aren’t many other football leagues where you can make a good living. What they can do and do do is go home, keep training, and wait for a phone call from an NFL team that may never come. When that call comes, more often than not, it’s for a place on a team’s practice squad. The practice squad or scout team is a group of up to ten players that a team can employ in addition to their 53-man roster. These players are usually used to imitate the tendencies and peculiarities of an opponent in practices for the week leading up to a game. Practice squad players are officially free-agents so they can be signed to the full-time roster by any team who likes them whether that’s the team whose practice squad they are on or not.

This whole process is physically and psychologically incredibly challenging for the players who go through it. Let’s lean on Siebert here for a feel of what it’s like to go through it.

First, players who have been the best of the best for their whole lives have to come to terms with their new status and struggle. As Schiller said to Siebert:

And then you come to the N.F.L. and, well, I’ve never felt so bad at a sport I know I’m good at.

Injuries are suffered in silence for fear of being tagged as injury prone or simply replaced with a healthier aspiring player:

There was no thought, he said, of seeking out a trainer. Everything a rookie does in camp is documented, and visits to the training room leave the wrong impression.“We have an expression here,” he told me. “ ‘You don’t make the club in the tub.”’

Injuries to great to hide are a marginal player’s biggest fear:

He picked up an empty bottle of anti-inflammatory pills and tossed it in the trash.“Even if I make it,” he said, “the average career is what, three or four years tops. But if I get hurt now, I’m gone. It’s nothing personal. If I’m injured, I’m dead weight. I’m stealing their money. Do you know how many linebackers there are sitting home right now that want my job? Hundreds. I mean, let’s get real. As much as Coach Smith or Coach Pires might like me, it would be: ‘Hey, it’s been a fun ride. You’re a good kid. But see ya, Schiller!’ ”

But they are also a source of great hope because an injury to an established player could make room for them on the team’s roster:

Pat sat bolt upright, grabbed the remote and scrolled back through the game to determine the precise moment James entered. He then went to the Falcons’ game thread on his computer, eyes narrowing, lips slightly parted in anticipation.“Stephen Nicholas,” he muttered. “Ankle.”For the next two days of my visit, we were on the Stephen Nicholas ankle watch.

What happened to Michael Sam?

Michael Sam was drafted in the seventh round by the St. Louis Rams. In some ways this was an ideal result for him. Coach Jeff Fisher is well-known as one of the more progressive coaches in the league. He was firm in stating that Sam’s sexual preference was not going to be an issue or a factor within the team and he has the standing to make most observers believe him. The Rams also have one of the best defensive lines in the league. Their two starters at defensive end, the position Sam plays, Chris Long and Robert Quinn, are as close to being household names as you can get playing that position. Sam was in a position to learn from the best but he also had a tough fight ahead of him to make the team. As Siebert writes in his article, “The math of making an N.F.L. roster seems straight forward. There are 40 or so players who are Ones and Twos on offense and defense. Then there is a punter, at least one kicker, a long snapper and often a third-string quarterback. This leaves just a handful of positions available.” Those positions often go, not to the next best player at a position, but to the player who can be most valuable to a team on their Special Teams’ units that return or cover kickoffs and punts. As a former star in college and a big dude at 261 lbs, Sam is at a disadvantage in this arena. He’s probably never played on a special teams unit before and players his size at his position usually do not.

Sam made it through the cut from 90 players to 75 but not the last one to 53 players. The St. Louis Rams cut Sam on August 30. He wouldn’t have long to wait before his next opportunity though. On September 3, the Dallas Cowboys signed Sam to their practice squad. The Cowboys have a less heralded defensive line but even so, Sam will be working hard on the practice squad, trying to impress without getting injured, probably needing an injury on the Cowboys or on another team in order to get signed. This is more likely than it seems. There have already been 113 players put on Injured Reserve or the Physically Unable to Perform list since the start of August. My guess is that Sam will play in an NFL game this year.

How typical was Sam’s experience? Did his sexual identity matter?

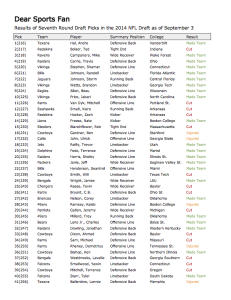

This is the hardest question to answer. From what I know, it seems like Sam’s experience was fairly normal for a player drafted in the seventh round. I did a little research on the 41 players drafted with Sam in the seventh round this year and of them 19 or just under half have already been injured or cut. Of the R ams’ four seventh round draft picks, none made the team.

ams’ four seventh round draft picks, none made the team.

The two questions that loom largest in my mind about Sam’s experience, both of which I cannot answer, are whether his sexual identity could have made him get drafted later than he would have otherwise (which would make it harder for him to make the team because the team perceives themselves as having committed less and sunk less cost into him) and how much the pressure of being a trailblazer may have affected his play in the pre-season.

Of course Sam’s sexual identity or more accurately, other’s perception of his sexual identity and the focus it created on him, affected his experience in innumerable ways. That said, I’m not sure we’ll ever know whether it may have changed Sam’s NFL outcome in the ways I suggested above. I hope, for Sam’s sake and for our sake as a culture, that Sam makes them a non-issue by playing well in the NFL later this season. If it’s not in the cards for him, I don’t think we’ll have long to wait for another brave, gay football player to come along.

Oh, and in case you were wondering what happened to Pat Schiller, the aspiring football player from the great New York Times magazine article? He’s still pursuing his dream. He was one of the players competing with Sam for a spot on the Rams this summer. He made the team as a fourth-string linebacker and special teams player.