Dear Sports Fan,

What is the red zone in football? The announcers during football games are always talking about one team or another being “in the red zone.” What does that mean? Do the rules change when a team is in the red zone?

Thanks,

Sammy

— — —

Dear Sammy,

The red zone is a term used to refer to the area from the twenty yard line to the goal-line of the side of the field that the football team with the ball is trying to score on. A team that is “in the red zone” is one that has the ball and is less than twenty yards from scoring. The red zone is purely a convention, it has no implication on the rules of football at all.

Wikipedia writes about the red zone, that it, “is mostly for statistical, psychological, and commercial advertising purposes.” In terms of psychology and statistics, you’ll often see statistics about how often a team scores once they are in the red zone and what percent of those scores are touchdowns versus field goals. Fans feel like once their teams are in the red zone, they should score. Missed “red zone opportunities” are seen as disappointing and as potentially pivotal to the result of a game. This psychological understanding of the red zone is true of at least some football players as well. Reporter Sam Borden asked a football player about the red zone in an article on the topic from 2012:

Tight end Martellus Bennett says the irritation a unit feels when a red zone trip goes unconsummated is unique.

Initially, Bennett hesitated when asked to describe the emotion that came with walking off the field with the ball so close to the end zone. “I’m not sure this is printable,” he said. He ultimately offered a “cleaned-up” analogy that likened it to the frustration felt by an anxious, apprehensive man who spends hours working up the courage to talk to a pretty woman and then is only steps away when another man sidles up and slips his arm around her.

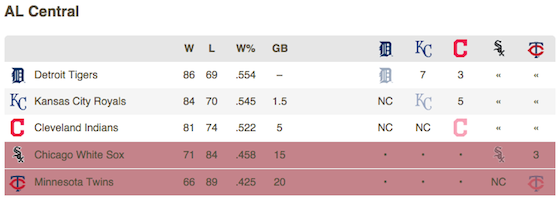

Sports statisticians have looked into the red zone and, for the most part, come up empty. As you might expect, there’s nothing magical about the 20 yard line that makes scoring easier or more likely once it is crossed. The best visual proof of this comes from NFL Stats Blog and it shows likelihood to score based on first down field position. Note that even the terms of this chart belie the red zone as a simple statistical reality because, of course it’s better to have the ball at the 22 yard line on first down than the 19 yard line on third. The likelihood to score curve is relatively smooth all the way down the field. A team in the red zone has a better chance of scoring as a team out of the red zone but there’s no statistical cliff that supports making a big deal over it. (As an aside, the most interesting part of the graph to me is that a team that gets a first down on the 11-15 yard line is more likely to score than if they get it on the ten yard line. This matches my instinct about football — it’s hard to go a full ten yards to get a touchdown — it’s better to at least be able to get another first down on the 1-5 yard line than have to score in one set of downs.)

No one seems to know exactly where the term comes from. One popular theory, which has floated to the top of this question on the sports question & answer portion of Stack Exchange, is that the term has military origins and means, “generally close to the enemy (red having been a symbol for danger for a long time).” I buy that as an explanation. Football has a long history of emulating the military. The same New York Times article from above, related a story about longtime New York Giants coach, Tom Coughlin, who early in his career:

Decided a psychological change of language was in order. Instead of describing the area as the red zone, Coughlin said, he consciously switched it to the green zone when referring to his team’s offense. His reasoning was simple.

“Green is go and red is stop,” he said. “What are you trying to do in the green zone? You’re trying to score. It’s not the red zone. If you’re on offense, it’s green.”

Coughlin’s got an interesting point. If you follow the analogy closely, the team in question seems to be the defending team, not the team playing offense. I think at some point, as football itself flipped to being far more about successful offense than successful defense, we flipped how we use the term red zone. My guess is that originally, the red zone was used primarily to describe the last twenty yards a defending team had to concede before allowing a score.

The red zone is a made-up concept but it’s a compelling one. Hearing that a team is in the red zone makes most football fans look up from their nachos (if they’re lucky!) and attend to the game. Some programming genius at the NFL thought about this and realized there was an opportunity to be had. The NFL created a television network called the NFL RedZone that springs from game to game on Sundays, showing every red zone trip all day, sometimes multiple games simultaneously. It’s a smashing success and will be the subject of a Dear Sports Fan post soon.

Until then,

Ezra Fischer