Dear Sports Fan,

My partner seems to really enjoy when an athlete gets hurt playing their sport. Usually it’s when it’s an opponent but sometimes even a player on the team he roots for. What’s up with that? Why do sports fans like injuries? Are they evil?

Thanks,

Violet

Dear Violet,

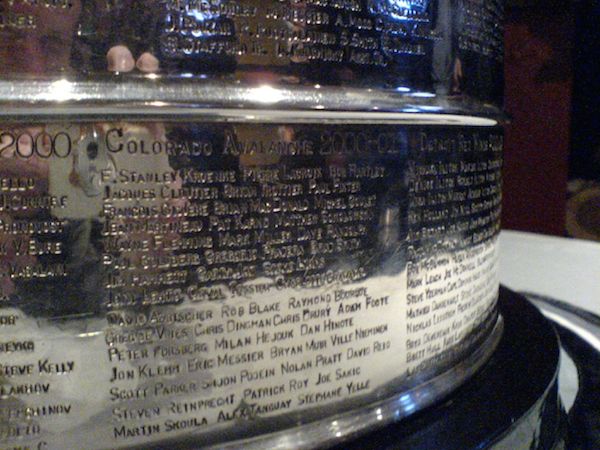

I’ve been thinking about this question a lot over the past couple of weeks, since the National Hockey League (NHL) playoffs started. Even though I’ve been a hockey fan for over twenty years now, the intensity, violence, and sheer excitement of the playoffs surprises me every year. Injuries are one of the most noticeable ways in which the playoff games differ from the regular season games. Hockey playoffs are set up as best four game out of seven series between two teams. During the course of one of these playoff series, the injury rate for players seems to approach 100%. Just off the top of my head, from the series I was following most closely, I can think of countless times when players got hit in the face with sticks or with the puck, injuries resulting from players blocking shots and taking the puck off a unpadded or insufficiently padded area, twisted knees, and crunched shoulders. And of course, the dreaded specter of concussions looms over hockey as it does every collision sport.

All of these things happen during regular season hockey games but not nearly as often as they do during the playoffs. Your question begs me to consider my love for the playoffs and their higher rate of injury — am I a masochist? or is there another reason for enjoying seeing other people get hurt?

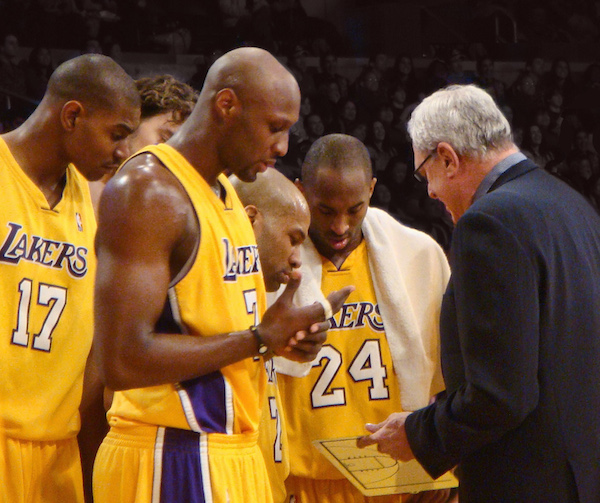

Over the years on this blog, I’ve suggested that one of the primary and primal reasons why people love watching sports is because they enjoy watching other people do things they absolutely could never do themselves. In this case, I think there’s another similar rationale that comes into play. People love watching sports because they enjoy watching other people do things they absolutely would never do themselves. The thrill of watching other people in danger and the admiration of our sport heroes courage are palpable. A hockey player who slides in front of a 100 mph slap shot, risking broken bones, smashed teeth, or worse simply to prevent his goalie from needing to make a save is doing something as unthinkable to most sports fans as LeBron James dunking a basketball or Bryce Harper hitting a home run. The distance between us and the hockey player is simply mental, not physical. Hockey injuries are a visual reminder of the mental distance between NHL players and normal fans.

The other aspect of enjoying injuries, especially in hockey, is that they, and how quickly hockey players return to play from suffering them, are a testament to how much hockey players care about winning. Sports fans live with the constant nagging fear that in the entire ecosystem of sports, they care more than the owners, coaches, general managers, players, and media members. It’s okay to be the person who cares the most about something, but when you care the most and have the least control over the outcome of something, you’re generally the rube. The way that hockey players play in the playoffs — recklessly, relentlessly, and despite injury — shows that they care just as much as the fans.

So, the next time your partner gets excited by blood dripping onto the ice, just know that he sees that as a sign that his passion is matched by the players he roots for and that he is admiring someone for doing something he would never, ever do.

Thanks for reading,

Ezra Fischer