You remember Deflategate, right? The controversy before this year’s Super Bowl that revolved around whether or not the New England Patriots and their quarterback, Tom Brady, intentionally deflated the footballs they were using on offense beyond the NFL’s regulations. The hubbub died down for almost three months while the NFL’s investigation was ongoing. Then, this past week, it exploded again as the results of the report and then the NFL’s decision about how to penalize the Patriots and Brady were made public. The report focused on Brady and stopped just short of saying that he definitely ordered Patriots personnel to illegally deflate the footballs. Whether you think this is the best hot topic since sliced bread or the dullest subject since the weather in Singapore, you’re likely to take part in at least a few conversations about Deflategate over the next few days. Here’s a few common comments and how to respond to them.

This penalty is great! Cheating is terrible and should always be punished with righteous fury!

I guess that’s true, but there’s also a very strong sense within sports that some types of cheating is permitted or even admired. Have you ever heard the phrase, “if you’re not cheating, you’re not trying?” That’s a sports phrase and it could easily be applied to minor cheating that’s accepted in sports. Here are some examples of acceptable cheating, just in football: wide receivers who put a little bit of sticky substance on their hands or gloves, offensive linemen who hold defensive players to keep them away from the quarterback, or even defenders who try to sound like the quarterback in order to throw the offensive line off their rhythm. All these things are officially illegal but we usually admire players who do this for being sufficiently motivated to win.

But we’re not talking about acceptable cheating, this is totally different!

I don’t think so. The NFL clearly wants quarterbacks to be able to customize the footballs they use on offense. If they didn’t, they would simply provide the footballs themselves instead of giving them to each team before the game to customize within a range of acceptable parameters. Modifying the football’s pressure is legal, the Patriots just did it too much — it’s an infraction of degree, not an original one.

Okay fine, maybe the original act wasn’t so bad, but Brady lied! He went in front of the American people and said he had nothing to do with this. Hypocrisy should be punished!

Hypocrisy is in some ways, the cardinal sin of our era. Our sense of morals has become so relative that we find it easier to condemn hypocrisy than any given act. This plays out most frequently in politics. A football playing holding a press conference may look like a politician holding a press conference but when it comes to hypocrisy, it’s entirely different. Politicians are and should be beholden to the public, we are their constituency and their employers, but football players are not. They’re under no particular job-related ethical obligation to tell the truth. Moreover, we actually expect players and coaches to lie all the time and condemn them if they don’t. For example, if Brady answered a question after a loss by saying that a teammate of his messed the game up by making a mistake and honestly sharing his frustration with that player, the sports media would come down hard on him for being a bad teammate.

How can the NFL suspend Tom Brady twice the number of games for deflating footballs than they originally tried to suspend Ray Rice for assaulting his fiancee?

For starters, it’s pretty clear the NFL acted idiotically in only originally suspending Ray Rice for two games. Two wrongs wouldn’t make a right, so why should we compare the two situations? Secondly, it is reasonable for a football league to punish players more severely for things they do that affect football than they would other infractions. Running a red light is far, far more dangerous than pass interference but that doesn’t mean the NFL should assess a larger penalty to a player who gets a traffic ticket than one who commits a foul on the field.

This penalty is a travesty. The report only concluded that Brady probably knew about the deflation, not even that he definitely knew or ordered it. How can they punish him?

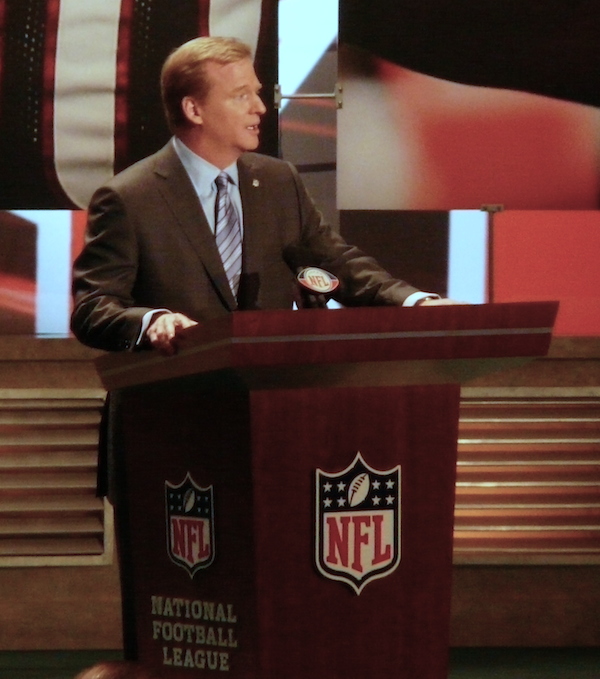

Hold on there, the NFL is not a court of law and Brady is not on trial. Principles like “beyond a reasonable doubt” and “innocent till proven guilty” don’t apply here. Brady is an employee of a company (the Patriots) that is part of a confederation of similar companies (the NFL). They can basically do whatever they want and it’s perfectly legal. Brady, as well as the other players in the NFL, are part of a union that collectively negotiates for how, when, why, and how much the NFL can punish players. They will almost definitely be appealing this penalty and they have a pretty good chance of getting it reduced. There’s no real victim here, it’s a dispute between a powerful employee and a powerful employer.