What’s the most dangerous place to be on a football field? Which positions put players in the greatest peril? What are the greatest contributing factors to the epidemic of brain injuries? Thanks to our post on what we know about the consequence of brain injuries in football, we know brain injuries are a serious concern. Today we’ll learn more about how they happen and what elements of football cause them. As a reminder, brain injuries are divided into subconcussive events and concussions. Both are problematic and both occur with disturbing regularity on a football field. Let’s take subconcussive events first.

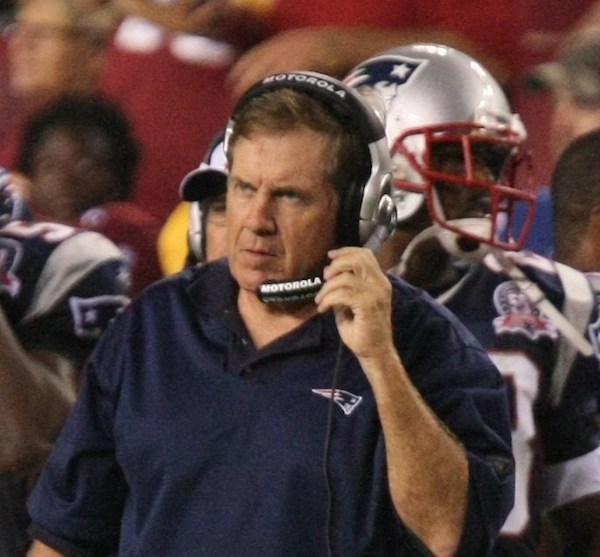

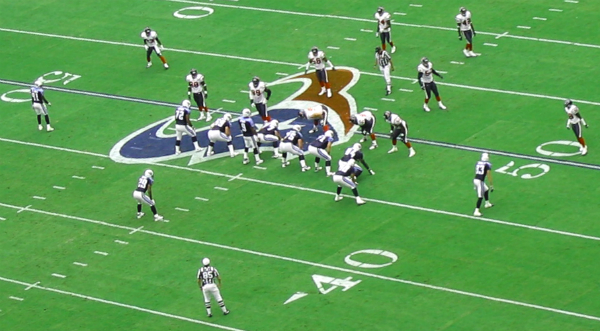

Subconcussive impacts happen all the time in football but significantly more frequently to some players than others. If you watch an average football play, you’ll see that it begins with two lines of three to six men lined up directly opposite one another. These players are the members of the offensive and defensive lines. These guys are huge, strong, and fast. They’re like Sumo wrestlers with armor on. When the ball is snapped, they launch themselves at each other, the defenders trying to get to the quarterback or to a running back with the ball, and the offensive line trying to protect their quarterback or to shift the defenders in order to create an opening for a running back to run through. Football people sometimes refer to the action that goes on between these players as the trenches of a football game and indeed, the action when it happens, is fast and furious.

It’s not alarmist to contend that players in the offensive and defensive lines suffer a brain injury on virtually every play. Here’s how Kyle Turley, the subject of a Malcolm Gladwell New Yorker article on brain injuries describes being in the trenches of a football game: “You are involved in a big, long drive. You start on your own five-yard line, and drive all the way down the field—fifteen, eighteen plays in a row sometimes. Every play: collision, collision, collision. By the time you get to the other end of the field, you’re seeing spots. You feel like you are going to black out. Literally, these white explosions—boom, boom, boom—lights getting dimmer and brighter, dimmer and brighter.”

It’s possible that other players don’t perceive the common subconcussive blows in the same way as Turley. It’s possible even that some players are able to withstand the repeated demands of being a lineman without having their brain injured on every play. To be conservative, let’s assume there is some level of brain injury, even if it is imperceptible, created by every collision of this type in a football game.

Other players on the field don’t hit or get hit nearly as often. A running back may get hit one in every two or three plays. A linebacker will be involved in a tackle one in every four or five plays. A cornerback or safety even less. Wide receivers may only get hit a handful of times in a game. When it comes to subconcussive blows to the head, we’re worried mostly about linemen, running backs, and linebackers. Counterintuitively perhaps it’s wide receivers and defensive backs that suffer the most concussions.

One of the most important things to know about concussions is that the “the amount of force and the location of the impact are not necessarily correlated with the severity of the concussion or its symptoms.” Rather, it is the “amount of rotational force” that is the key cause of concussions. As this CBS news article suggests, because of this fact, football helmets may not actually do much to prevent concussions. Concussions are the result of “rotational injury… when the head rotates on the neck because of the impact, causing the brain to rotate.” Helmets do a great job of protecting against skull fractures and do a good job of preventing or lessening the impact on the brain from linear impacts that occur when a player is straight backwards.

This means that players usually do not get concussed if they can see a hit coming and have the time and freedom to prepare for the hit. A player who is hit under these ideal circumstances will face the hit, aligning his body to receive a linear as opposed to a rotational impact. The player will brace his neck, so that the force of the blow is distributed from his head, through his neck to his body. Given time, most football players can protect themselves from concussions.

Football players who do get concussions get them most frequently when they don’t see the blow coming or when they aren’t prepared for the hit. This could happen either because they don’t have time to prepare or because they choose not to for the sake of the game. Just from watching countless football games, you get a sense for which collisions are more likely to cause concussions. Those times a running back plows right into a handful of defenders and drags them a few feet before falling? They almost never result in a concussion. How about when quarterbacks are hit while throwing the ball? These hits are more likely to result in broken ribs or collarbones than concussions. In both cases, the players usually know the hit is coming. What about at the end of a play when a player on the ground is just clipped by the knee of a player running by him? That’s a problem! What about a wide receiver who leaps to catch a ball only to be met in mid-air by a defensive back catapulting himself at the receiver? Houston, we definitely have a problem, often for both players. How about a so-called blind-side hit when a player is hit from one direction while looking in the other? You guessed it, those cause concussions too.

The recurring themes for hits that cause concussions are speed and chaos. Football players get concussions most frequently from hits that they don’t know are coming or when the play is too fast for them to do their job as football players and to protect themselves. The speed and chaos of modern football have overrun the brain’s ability to track and prepare for collisions, even for the best athletes in the world.

Even NFL players agree with this suggestion. James Harrison has been one of the most obvious villains of the recent era in the NFL. A veteran linebacker who played most of his career for the Pittsburgh Steelers, Harrison is known as a reckless hitter who, even for football, was known for launching himself dangerously at opposing players, using his head as a weapon. In Ben McGrath’s 2011 New Yorker article, Harrison defends himself by blaming the speed of modern football for his acts. “The game’s a lot faster than it was when [NFL director of game operations, Merton Hanks] played… When we’re right there, and it’s bang-bang, you don’t have time to adjust.”

Speed + Chaos = Concussion. It seems now like an inevitable conclusion. If we take that equation for fact, the important question becomes, how can we change football to protect its players without losing the sport’s essence? Malcolm Gladwell phrases the question like this: “How do you insure, in a game like football, that a player is never taken by surprise?” We’ll eventually answer that question in this series of articles on how to fix football. In our next installment, we’ll describe why it’s necessary to deal with this issue at all. Why should football care about brain injuries?

Dear Sports Fan provides resources for living in harmony with sports. If you enjoy our content, please share it with your friends and family. If you haven’t signed up for our newsletter or either of our Football 101 or 201 courses, do it today!