Dear Sports Fan

How does stealing bases work in baseball? I know that a stolen base is when a player runs from first to second or second to third base without there being a hit but I’m not sure when base runners can steal and what situations they do it in. Can you help?

Thanks,

Andres

Dear Andres,

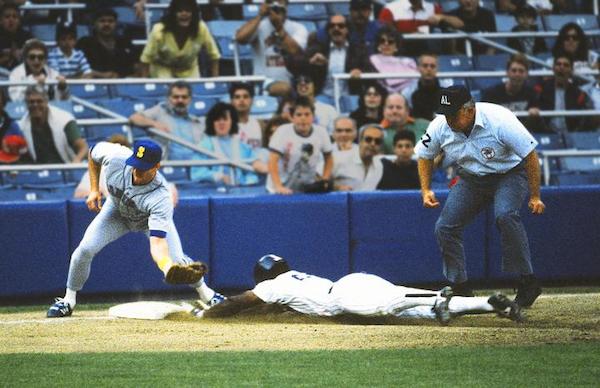

The steal is one of the most exciting plays in baseball. A player on base tries to run to the next base without the assistance of a teammate’s hit. If he gets there before the opposing team can throw the ball to the base and tag him, he’s safe. If not, he’s out. It’s got speed, deception, timing, and coordination — everything you could want in a sport. A successful stolen base can propel a team to victory. An unsuccessful one can break a team’s momentum and destroy its chance of winning. So how does a steal work?

A player on base — that means they got to first, second, or third base through hitting the ball, being hit with the ball, or being walked — can try to run to the next base basically whenever they want. The only time they are not allowed to run is if a timeout has been called. Timeouts are not as obvious in baseball as they are in other sports, probably because they are unlimited, but they usually happen when a batter steps out of the batting box and holds up his hand or when a catcher wants to speak to his pitcher or visa-versa. If you’re at a game or if you have your television volume way, way up, you might be able to hear the ump screaming, “TIME” when someone gestures for a timeout and “PLAY” when the timeout is over. In some recreational baseball or softball leagues, a timeout is called by default whenever the pitcher has the ball. Not so in a professional setting.

The fact that base runners can try to steal virtually whenever they want doesn’t explain much about when players actually attempt to steal. Professional baseball players throw so accurately and strongly that unless a runner caught them completely off-guard, stealing in the normal course of play would be a miserable and ineffective gambit. No, what makes stealing possible is a rule that forces pitchers to throw the ball to home plate once they’ve committed to the motion of throwing in that direction. A pitcher who is guilty of starting to throw to home plate and changing his or her mind in mid-pitch is guilty of what’s called a “balk” and any players already on base get a free trip to the next base. The impact of this rule is that it allows sharp eyed, speedy players on base to watch the pitcher and start running to the next base as soon as the pitcher commits to a pitching motion.

Once a player decides to steal a base, she begins sprinting to the next base. She only has a few seconds to make it there. In that time, the pitcher will pitch the ball over home plate, the catcher will grab it, rise to his feet, and throw to the player covering the base the runner is trying to get to in one motion. The whole thing – running from one base to the next as well as the pitcher and catcher combining to try to throw that player out – takes right around 3.5 seconds. In a Smithsonian Magazine piece, Brad Balukjian describes an analysis of the process that suggested the most important factor in a successful stolen base is the top speed a runner reaches in his attempt.

By far the most common base players try to steal is second base. There are a few reasons for this:

- Singles are by far the most common hit. Therefore being on first base is more common than being on any other base. From first, the only place to go is second.

- While there are more lefties in professional baseball than in the general population, there are still more right-handed pitchers than left-handed ones. When a righty sets up to pitch, his back is turned to first base. This gives the base runner an advantage stealing from first to second but a disadvantage going from second to third.

- As we covered in out article explaining why there are so few triples any more, there simply isn’t that big of a difference between being on second or third. Runners on either base are expected to be able to score on a ball hit out of the infield and not on one that stays in close. Stealing third isn’t often worth the risk. The difference between being on first or second, on the other hand, is a big deal and worth a greater risk.

While the rules about how and when a player can steal a base are fairly simple the rules about when their act is deemed to be an official steal by scorekeepers is much more complex. While it may not seem important (no matter how it happened, what matters to who is going to win is that the player made it from first to second or second to third) baseball players, managers, and true fans give statistical designations like this a lot of importance. Just one example of these distinctions is that a player who makes it safely to a base because the catcher threw the ball wildly in her attempt to catch the runner stealing is credited with a steal while a player who safely gets to the next base because the opposing player who was trying to catch the ball and tag him out messed it up, he is not credited with a steal.

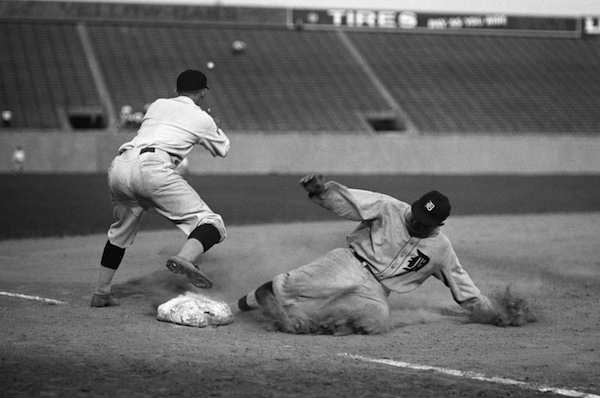

Aside from stealing second from first and third from second, there are three other forms of stealing that are much more rare. A player on third base can attempt to steal home. This sounds insane, since to catch the player, the defensive team only needs to do half or one third of the stuff they normally have to do to catch a stealing attempt. Instead of the pitcher throwing it to the catcher who throws it to a player covering second or third base, the pitcher just needs to get the ball to the catcher who can stand there and tag the runner out. Only the fastest and most audacious players ever dream of attempting this. Jackie Robinson did it successfully in the 1955 World Series. A double steal is a play where two runners on different bases both try to steal the base ahead of them simultaneously. This can involve players on first and second running to second on third but it can also be used to disguise an attempt to steal home. The last form of rare stolen base is not allowed any more. In the early days of baseball, when entertainment and high-spirited hijinks were as important drivers of behavior as winning, base runners would sometimes steal backwards. This behavior is now prohibited by MLB rules and somewhat sassily too: if a player “runs the bases in reverse order for the purpose of confusing the defense or making a travesty of the game. The umpire shall immediately call Time and declare the runner out.”

Thanks for your question,

Ezra Fischer