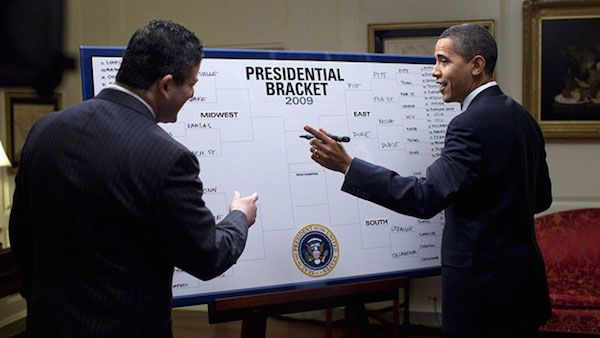

March Madness, the NCAA college basketball tournament, is one of the most highly anticipated sporting events of the year. Aside from furtively watching games on laptops, tablets, or phones during work, the most common way that people interact with the tournament is through the filling out of March Madness Brackets. Doing a bracket is a form of gambling. Before the tournament begins, a bunch of people get together and (usually using some web software) each predict what they think is going to happen in each of the 67 games during the tournament. Rules vary a little from one platform to another and one group to another, but generally you get points for correctly predicting the winner of a game and those points increase as the tournament goes on. For instance, you might get one point for predicting a game during the first round of the tournament but twenty points for getting the winner of a Final Four or semifinal game right. By and large, brackets are a fun way to get involved with the tournament. It keeps you interested in what’s happening and usually it’s not for enough money to be a problem if you lose.

To help prepare you to fill out a bracket this year, we thought we would explain some common, uncommon, serious, and frivolous ways to fill one out. Today we’re starting with chalk.

Chalk is the simplest way to fill out a March Madness bracket. In every game, simply take the team with the better seed. Here’s a quick explanation in case you don’t know what that means. The 64 teams that will start the tournament on Thursday are divided up into four groups of 16 teams each. Within each group, the teams are ranked or seeded from 1 to 16 with the number one team being the most accomplished and likely to win and the number 16 team being the least. In the first round, 1 plays 16, 2 plays 15, 3 plays 14, and so on. Taking chalk means that you pick the team with the better seed (lower numbers are better) in every game.

This term is widely used but doesn’t seem to have a clear derivation. The New Republic and Visual Thesaurus both believe it comes from a time when most betting was done in person at horse races and the odds were maintained by a bookie with a blackboard and a piece of chalk.

The benefit of picking chalk is that you’re almost alway going to be in the running to win your bracket pool. The downside is that you’re almost guaranteed not to win. Chalk is something of a default strategy. Although very few people choose all chalk for their entire bracket, for any given game, more people are going to predict the team with the better seed to win than to predict an upset. Choosing all chalk means that you get the points that most other people get but you’ll never get a point that they don’t. As time goes by, you’ll settle into the top third of the entries but won’t have a very good chance of winning the whole thing. Someone who predicts even a single upset correctly will probably have a better score.

Of course, sometimes chalk is a good idea. Imagine you were playing against only one other person and you knew that she was going to pick a bunch of upsets. By taking all chalk, you’d be pitting her ability to predict the future against the NCAA Tournament selection committee. And that’s a bet, I’d be willing to take. The smaller your bracket pool, the more likely it is for an all-chalk bracket to win. In a larger pool, it’s basically impossible that one of the entries won’t be better than chalk by accurately predicting a major upset.

I’m sure someone more well versed in mathematics or economics could explain the logic of chalk not winning better than me. What I can add to the discussion though, is that picking chalk is less fun than other strategies. One of the best parts of watching college sports and particularly March Madness is that emotion can often carry an underdog to a victory against an overdog. It’s more fun to root for a 13 seed no one has ever heard of with players that won’t make it in the NBA than it is to root for the 4 seed they play against whose players and coaches are virtually professional already. If you choose all chalk, you don’t get to root for upsets and rooting for upsets is fun.

Tune back in later for more (and more fun) ways of filling out a bracket.