Soccer has always has an air of “otherness” in the United States. It’s the major world sport we are the worst at. Somehow in the 1960s or 70s, it became culturally associated with the liberal political leanings that often went along with an inclination towards international and particularly European ideas and culture. Unlike ice hockey, which is still primarily a Canadian and European sport, the best soccer leagues in the world do not reside in the United States. For all these reasons, soccer terminology remains opaque to many casual fans or non-fans of the sport. To help with this problem, here are definitions for the 20 most common strange soccer terms.

- Cap – Not part of a team’s uniform (or kit — bonus word!), a cap is an appearance on a country’s national team. The number of caps a player has is used as a sign of how experienced she is.

- Nil – Fancy sounding word for zero. Used by British and Anglophilic soccer fans.

- Pitch – The field of play. As in, the place you would pitch the ball from if you were playing baseball or cricket.

- False nine – Soccer has a traditional system or systems of numbers that refer to positions. Nine is the striker or forward. A team is said to be using a false nine when their farthest forward player frequently drops back farther than a normal striker would.

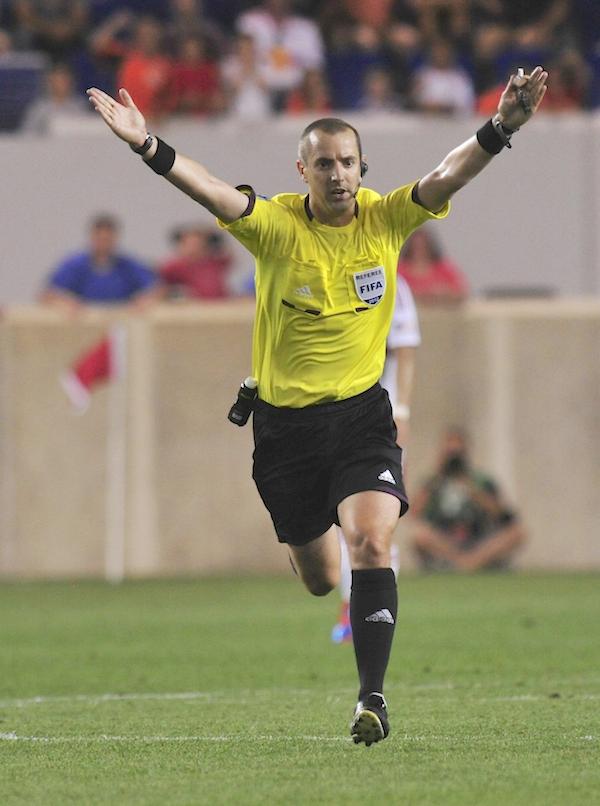

- Stoppage/injury/added time – Soccer is the only timed sport whose official clock is kept secret during the game. Only the ref knows how much time is really left. Stoppage time, injury time, and added time are all phrases used to refer to the period between when 45 minutes have elapsed from the start of a half to when the referee blows her whistle to end the game. The ref announces an estimate of how many minutes this will be at the end of each half but he is not held to it.

- 4-4-2 – A common soccer formation. In numerically expressed formations like this, the numbers refer to the players in each level of play, starting on defense, right after the goalie. 4-4-2 is four defenders, four midfielders, and two forwards.

- Clean sheet – Close to synonymous with a shutout in American sports. Credit for a clean sheet is usually given to a team’s goalie and defenders. Some may even have contractual bonuses for clean sheets.

- Switch the field – To pass the ball a long way across the field. An attacking team may switch the ball from the left side to the right if they aren’t having success creating offensive chances on the original side.

- Golazo – An unusually beautiful goal. The creativity and technical excellence of the goal matter more for qualification as a golazo than the importance of the goal.

- Nutmeg – When one player tricks another player by passing, shooting, or dribbling the ball between their opponent’s legs. The term’s derivation is disputed but one great theory involves spice counterfeiting.

- Parking the bus – When one team commits all their resources to defending. This can be a good strategy against a superior team. The U.S. Women’s National Team expects that a lot of their opponents will play this way against them.

- Advantage – If a team has a foul committed on them but would be disadvantaged by stopping the game, a referee can choose to play or call advantage and let the play continue. If the foul warrants a yellow or red card, the ref can give the offending player her card the next time the game stops.

- Professional foul – An intentional foul committed by a player (usually a defender) to prevent a scoring chance. The best professional fouls are ones that anticipate the action by enough to avoid being penalized specifically for taking a scoring chance away from the other team.

- Through ball – A pass that is designed to go behind the opposing team’s defensive line where it can be picked up by a teammate of the player passing the ball.

- Tiki-taka – A style of play, popularized by the Spanish men’s national team, that relies on high volume, relatively safe short passes to move the ball and maintain possession. World soccer seems to be at the tail end of a time when this style was ascendant.

- Woodwork – The goals may no longer be made out of wood, but the goal posts (sides) and cross bar (top) are still referred to by their original material. A shot that hits the goal may be said to leave the “woodwork” ringing.

- Work rate – An imaginary stat that refers to how hard a player is playing. Technology has recently made it possible to quantify part of this by tracking how far each player runs during a game. Central or defensive midfielders usually have the highest work rates and sure enough, they usually run the farthest.

- Overlap – A common track a player might run in relative to her teammate who has the ball. Overlapping or running an overlap is to run between the player with the ball and the sideline, from behind the player to ahead of her. This serves to give the player with the ball a passing option and also to stretch the defensive players farther away from each other by forcing one of them to follow the player making the overlap run.

- Booking – When a referee disciplines a player by giving him a yellow or red card. Two yellows in one game or a single (called a straight) red means immediate expulsion from the game. After being expelled, the player’s team has to play the rest of the game down a player, they cannot add a substitute.

- Cynical – A play that violates unwritten rules. On offense, this usually applies to flagrant simulation or diving. On defense, this is normally a professional foul. A foul need not be violent to qualify as cynical.