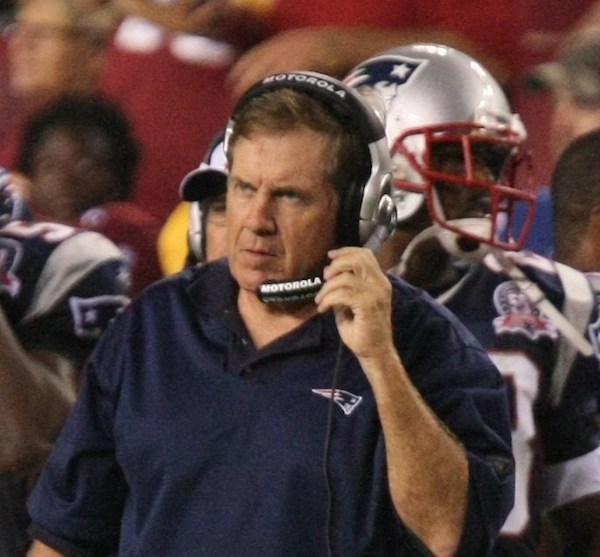

In the week leading up to Super Bowl XLIX, we’re profiling the important characters of the game. We’ve already run posts on New England’s coach, Bill Belichick, quarterback, Tom Brady, and the rest of the New England Patriots offense. Now it’s time to learn a little about the New England Patriots defense.

Vince Wilfork, Defensive Tackle

Vince Wilfork is the giant heart of the New England defense. He plays nose tackle, which means he uses his enormous weight (listed at 325 lbs but looks more like 365 lbs) and athletic ability (he claims he can still dunk a basketball) to fight against double-teams from opposing offensive linemen to get to the quarterback or running back. He’s an elder statesman of the Patriots, at the age of 33 and having been a part of the team since he was drafted in 2004. As much as you can tell from watching someone on television who is usually wearing a helmet, Wilfork seems like a really awesome guy. He’s often smiling and joking on the sidelines. He apparently had a practice of finding the Patriots owner, Robert Kraft, and his wife Myra, before games and kissing them each on the cheek. After Myra died of cancer in 2011, Wilfork took to kissing Robert Kraft on both cheeks to keep up the tradition. In the Super Bowl, Wilfork will be an important part of the Patriots defense against the Seahawks strength on offense — running the ball. Find the enormous man wearing #75 for the Patriots and watch him. If he’s driven backwards, it’s bad news for the Patriots and good news for the Seahawks.

Chandler Jones, Defensive End

One of the ways the Patriots have managed to continuously stock their team with great players despite almost never picking at the top of the draft is that they look for hidden gems. Chandler Jones was a gem, partially hidden in the 2012 NFL draft because of a hip injury that caused him to miss half of his last college season at Syracuse. No matter, the Patriots swooped him up with the 21st pick of the draft. 6’5″ and 265 lbs, Jones is an incredible athlete from an athletic family. Of his two brothers, one is also in the NFL and the other is a champion mixed martial artist. Jones is at his best when he is aggressively attacking the quarterback. The Seahawks might try to use that against him by either running the ball right at him or by running read-option plays towards his side. During a read-option play, the quarterback can punish an over-aggressive defensive end by suckering him into trying to tackle him and then handing the ball to a running back who runs around the defensive end. Jones will have to balance his aggressive play with needing to make sure no one with the ball gets around him by mistake.

Jamie Collins, Linebacker

In addition to looking for hidden gems, the Patriots favor versatility over almost everything. Jamie Collins is one of the most versatile defensive players in the NFL. He played at all three levels of defense (defensive line, linebacker, and defensive back) in college for the Southern Miss Golden Eagles. On the Patriots, he mostly plays linebacker, the position behind the big guys up front on the line of scrimmage but in front of the small guys in the defensive backfield. From this position he can use the full range of his wide skill set. On some plays he’s sent to attack the quarterback, on others he will cover a tight end or wide receiver. He’s one of the main candidates for players to “spy” Seattle quarterback Russell Wilson. This means he would be assigned the task of following Wilson around as he moves from side to side to make sure that if Wilson decides to run with the ball instead of throw it, he doesn’t get very far.

Brandon Browner, Cornerback

Brandon Browner is an interesting figure in this particular Super Bowl matchup. He was a member of Seattle’s so-called Legion of Boom defensive backfield for the previous three years before being signed this past Summer by the Patriots. In some ways, he still fits more with that group than with the tight-lipped Patriots. Browner is extremely tall for a cornerback, at 6’4″ and physical, sometimes to the point of taking unnecessary penalties. He has had a history of performance enhancing drug and substance abuse suspensions and actually missed playing in last year’s Super Bowl because of a suspension. He made a little bit of news this past week when he told the media that the Patriots should and would be targeting the injured joints of two of his ex-Seattle teammates.

Darrelle Revis, Cornerback

Darrelle Revis is one of the premier cornerbacks in the league. You may have heard the phrase, “Revis Island” and if you haven’t, you probably will this Sunday. That phrase, which Revis has apparently trademarked, expresses both the plight of the wide receiver that Revis is covering and his value to the Patriots. Revis is usually asked to cover the best wide receiver on the opposing team and unlike most other corners, he rarely has the safety net of another defensive player helping him with the assignment. Being assigned to cover someone one on one is a like being out on an island by yourself — you’re exposed, with no one to help you if you get into trouble. Revis is so good at it though, that the effect is often to make the wide receiver feel like he is on an island with no connection to the rest of his team and no way off. Quarterbacks often choose to ignore the receiver Revis is covering rather than challenge him by trying to throw to that receiver.

Prepare for the Super Bowl with Dear Sports Fan. We will be running special features all week to help everyone from the die-hard football fan to the most casual observer enjoy the game. So far we’ve profiled Seattle Seahawks coach Pete Carroll, New England Patriots coach Bill Belichick, New England Patriots quarterback Tom Brady, Seattle Seahawks quarterback Russell Wilson, the New England Patriots secondary offensive characters, and the Seattle Seahawks secondary offensive characters. If you haven’t signed up for our newsletter or either of our Football 101 or 201 courses, do it today!