I was on the sports-only social networking site Fancred a few days ago and I saw a post showing a photograph of Anthony Ujah, a Nigerian striker playing on a German soccer team. Ujah had just scored a goal and, in celebration, had raised his jersey to reveal a white undershirt with a handwritten message, “Eric Garner #can’tbreathe #justice”. I quickly upvoted (Fancred’s version of Facebook’s like) and then looked down at the comment thread below the post. Another Fancredder had posted a brief complaint. “Should stay out of sports”, he wrote. The original person who posted the photo challenged him by asking, “Then where can we discuss racism and injustice?” The answer from the commenter was, “Not on FANCRED and not on the field.. Do it after the game there are other ways to deal with this.”

This conversation got me pretty worked up. This view of sports as a refuge from social issues is a common one but not one that I believe holds any historic accuracy or moral righteousness. Sports has often been a forum for social or political expression. Just in my lifetime, I’ve witnessed the rise and mainstream reaction against the “hip-hop” athlete as personified by basketball player Allen Iverson. I’ve seen Jason Collins’ coming out as the first active male athlete in one of the “big four sports”. I’ve seen issues as wide-ranging as dog-fighting, gender equality, gender testing, using the N-word, and xenophobia played out in the context of sports.

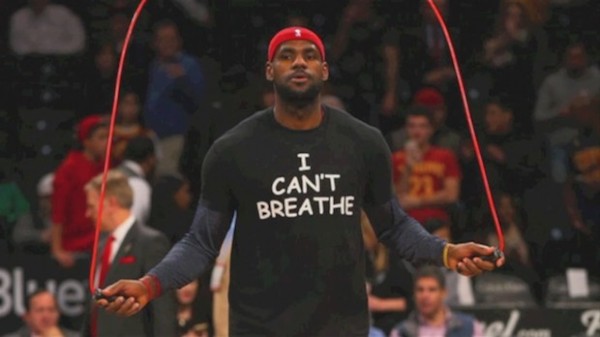

Sports in America, even with a Black president, are home to the most visible African-Americans in our society. Insofar as the issues underneath the Eric Garner, Michael Brown, and Tamir Rice cases are racial, it makes sense that they are discussed in the context of sports. In the last few week, athletes in football, basketball, and as we saw above, even soccer, have been making that point for us by reminding us of these issues before and during games. Four St. Louis Rams players came out on the field before a game with their hands held in the air, a symbol of protest in the Michael Brown Case. Basketball players, starting with Chicago’s Derek Rose, moving to LeBron James, Kevin Garnett, and several other Cavaliers and Nets, and continuing with the entire rosters of the Los Angeles Lakers and Georgetown Hoyas have worn “I can’t breathe” T-shirts during warm ups. Even lesser known players got in on the action, like Ariyana Smith of Knox College who was initially suspended for her protest preceding a game in Clayton, Missouri, where the Michael Brown grand jury was, and Johnson Bademosi of the Cleveland Browns, who wore a handmade shirt with the same message during a game and wrote about why in The MMQB later.

There have certainly been times when sports has been a refuge for some people, including African-Americans, from the worst forms of discrimination in society, but the argument that sports should be a refuge from the discussion of social issues is simply wrong. Sports has not ever been, nor should be a refuge from actively participating in social issues.

As I thought about this and made that case in my mind, I realized that I was not exactly living up to my own ideals. I have a platform (small though it may be) in Dear Sports Fan that I write in every day and which every day is seen by hundreds of people but I had not used it to express my own opinions about Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, the police that killed them, and the local legal response to their deaths. So, whether it’s my responsibility, my choice, or my privilege to use Dear Sports Fan as a platform for my thoughts on the issues of police violence and the legal system’s response to it, I am going to go for it.

Here’s what I think:

• I’ve been wondering why Eric Garner’s case has captured my passion more than Michael Brown’s or the many other incidents of police brutality. There are several reasons. First, Garner was killed in New York, where I live, so his death has more immediacy for me. Second, the results of the grand jury proceedings about his death were just that, second — they came out right after the Ferguson grand jury had primed us to react in a particular way. Third, while it’s possible for me to imagine (rightly or wrongly) Michael Brown’s killing as the result of misguided panic, the killing of Eric Garner is much harder to rationalize. Oh sure, the police who attacked him were never intending to kill him, but the use of a prohibited choke hold which there have been over 1,000 complaints to the police about in the last 5 years, is not the result of a momentary and unfortunate lapse. No, the choke hold that killed Eric Garner is a symptom of systemic abuse on the part of a police force that suggests a cynical negligence for the wellbeing of the public. The last reason why Eric Garner’s death was so striking is one that we sports fans should be familiar with: video. There was video of Eric Garner being killed but none of Michael Brown. Video is so powerful. It’s a key reason why the sports world was stirred up so much more by Ray Rice’s domestic abuse crime than by previous incidents. For that matter, it’s most of why you’ll find many more sports fans who think Michael Jordan was the greatest basketball player ever than who argue it was Bill Russell or Wilt Chamberlain, whose 100 point game is captured only in a photograph, not on video.

• I’m afraid we have too many of the wrong people in our police force. Police should be people so passionately opposed to violence that they are willing to devote their lives to preventing violence and catching people who perpetrate violence on others. Police should not be people with violent tendencies who seek to have their nature legitimized. While I am sure that there are many police of the first sort, it doesn’t seem like we have sufficient skill at avoiding the second type of police recruit or of weeding them out of active duty before they are able to be violent from the privileged position their badge grants them. This issue is not dissimilar to the one we face in politics where it seems as though anyone honest and upstanding enough to be a good congressperson or governor is so turned off by the rampant corruption and selfishness in politics that they never enter the political arena. Like in politics, fixing this problem in the police force is going to be a slow, probably even a generational process but it needs to start now.

• Seeking justice from federal authorities in cases of police violence is not good enough. I find it incredibly depressing that this is what leaders of the movement for justice from Al Sharpton to Letitia James were calling for immediately after the Eric Garner grand jury result came out. I understand the dynamic between local prosecutors and police involves close cooperation and mutual support but that is not an excuse for gross misbehavior. I’m unwilling to simply take the past, current, and future refusal of local prosecutors to indict police accused of violent crimes as a given. I’m a fan of movies and television shows about crime on the organized spectrum like The Godfather movies, The Sopranos, and The Wire. One of the redeeming qualities of the cultures that those shows represent is that even in the murky moral world of the Mafia or of drug dealers in Baltimore, there is a shared moral code with boundaries. There are lines beyond which even people who will go to jail for decades without identifying their friends or kill someone on command without questioning why will not protect you if you cross. Why is that not true for police and local prosecutors?

If St. Louis County prosecutor, Robert McCulloch was as sympathetic towards the policeman, Darren Wilson, as his twisting of the grand jury process suggests, then I think he should have started a fund for Wilson’s family. He could easily have seeded it with $5,000 or $10,000 of his $160,000 in base annual salary or if he really wanted to make a statement, he could have promised to give a whole year’s salary to the policeman’s family. I would have no problem with him using the celebrity the case has given him to express his support of the police or of Wilson in particular. But he had to do his job. He had to apply the same standards to Wilson as any other person accused of a violent crime. McCulloch didn’t do that just the same way that the public prosecutor in the Eric Garner case, Dan Donovan, didn’t do his job. Seeking justice from federal authorities may work in individual cases like these but relying on them as a permanent solution is an admission that local systems are immoral and irrevocably broken.

• Why don’t we have stats on police violence? Last week, when the Eric Garner non-indictment became public and the streets filled with protesters, I was stuck in my apartment with a fever. It was frustrating because this was the first time in my life I had ever felt clearly and unambiguously about an issue to want to join in a public protest. Stuck at home as I was, I spent a lot of time reading on the internet about the case and I came across something which is unbelievable to me, particularly as a sports fan who has witnessed the statistical revolution in sports over the past twenty years: there are no reliable national statistics about people killed in interactions with law enforcement. This is something which a man named D. Brian Burghart is trying to fix. He’s been working for the past two years on creating a database of people killed in interactions with law enforcement and he wrote about his experience in this article for Gawker. His conclusion, which he admits he cannot prove, is that “The lack of such a database is intentional. No government—not the federal government, and not the thousands of municipalities that give their police forces license to use deadly force—wants you to know how many people it kills and why.” If you’re inspired to donate, as I was, you can do that here.

I know there are far more knowledgable people, far more passionate people, and far better writers than me expressing themselves about these issues but there’s also power in all of us doing our part to make this issue stick around for longer than the normal two-week news cycle. I hope that we all find ways to keep this issue alive until we can transform our society into a more completely fair one. I know that’s a big, long project but it’s an important one as well.

Thanks for reading,

Ezra Fischer