Dear Sports Fan,

What does it mean to throw the ball away in football? I’ve been watching some football and I’m not totally ignorant about the game, but this phrase has always confused me. I know there’s a foul for intentional grounding. How can throwing the ball away be a good thing if there’s a foul for it?

Thanks,

Diane

Dear Diane,

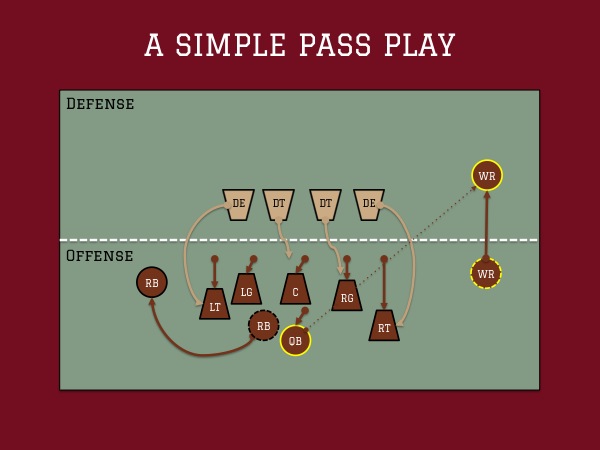

Throwing the ball away in football is what a smart quarterback does when he scans the field and realizes that none of his wide receivers or tight ends are far enough from a defender to safely throw the ball to. The cost of an unsafe throw can be very big. If a defender catches the ball (called an interception,) the quarterback’s team loses possession of the ball. On the other hand, throwing the ball where no one can get it simply results in an incompletion. It wastes one of the offensive team’s downs (or chances they have to advance the ball) but that’s usually not a big loss. The trick is, as you mentioned, that sometimes simply throwing the ball to no one is illegal and the cost for being caught intentionally grounding the ball is severe. Let’s go over the rule and then look at ways that football team’s skirt the rule so that they can throw the ball away without being penalized.

The intentional grounding rule reads as follows:

Intentional grounding will be called when a passer, facing an imminent loss of yardage due to pressure from the defense, throws a forward pass without a realistic chance of completion.

Intentional grounding will not be called when a passer, while out of the pocket and facing an imminent loss of yardage, throws a pass that lands at or beyond the line of scrimmage, even if no offensive player(s) have a realistic chance to catch the ball (including if the ball lands out of bounds over the sideline or end line).

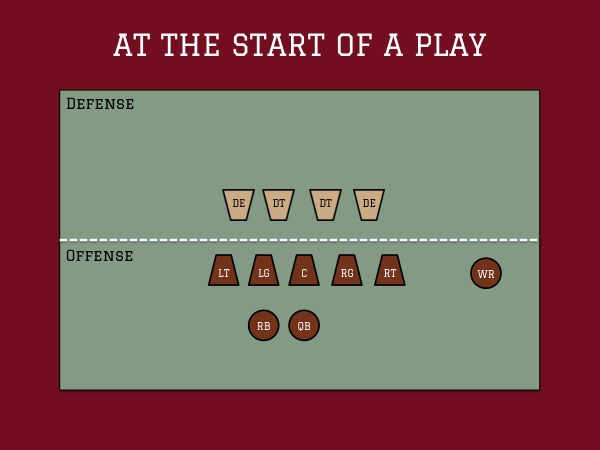

So, what does all that mean? First of all, it establishes the rule as subjective. It’s up to the referees to decide whether or not a pass has a “realistic chance of completion.” This is a funny thing when you think about it, because football players make catches routinely that have fans leaping out of their chairs and screaming in disbelief. One of the reasons to watch football is to see great athletes doing things that seem unrealistic. The subjectivity is necessary because the intent of the rule is to penalize quarterbacks for intentionally throwing the ball where no one can get it. So, we assume that football refs are used to what players can and can’t do, and we move on. The second thing this rule does is that it carves out a scenario where it’s legal for a quarterback to throw the ball fifty yards up into the stands if they feel like it. If the quarterback is “out of the pocket” he’s allowed to do this. The pocket is defined as an area starting where the offensive line lines up for a play and extending back from the left tackle’s left butt cheek and the right tackle’s right butt cheek into infinity. All a quarterback needs to do to be within his legal rights to throw the ball away is to run outside of that area and make sure he throws it past where the ball was when the play started. This keeps him from throwing it straight into the ground but it’s not much of a safeguard because quarterbacks can almost always reach the sidelines with a throw, even if they are actively being mugged.

Nonetheless, you’ll hear commentators complementing quarterbacks who throw the ball away from the pocket or chiding those who don’t all the time. This is because it’s totally common and accepted for a quarterback to throw the ball far enough from a receiver that it’s going to be safely incomplete 99.5% of the time but near enough to a receiver to establish the plausible deniability needed to avoid a penalty. As you watch football, you’ll learn to identify these times. A common scenario is a screen pass where the offensive team pretends to block as if they were protecting the quarterback but do it poorly enough to invite the defenders to overextend towards him. Then the quarterback is supposed to flip the ball over to a running back lurking several yards to the side, hopefully unnoticed by the defense. If any defenders catch on to this or “sniff it out” in football talk, the quarterback is in a tough spot because he’s about to get smashed by defenders who have been intentionally allowed a clear path to him but he has nowhere to safely throw the ball. Quarterbacks in this situation routinely throw the ball hard into the ground near the running back’s feet. Everyone knows he meant to do this but everyone also accepts that he won’t be penalized for it because the running back, acting as a potential pass receiver, was in the area where the ball hit the ground.

There’s a sports cliche that suggests that “if you ain’t cheating, you ain’t trying.” Throwing the ball away lives in that murky grey area between legal and illegal. It’s an area that leaves fans of a quarterback who throws the ball away feeling proud of him without qualms, even while fans of their opponents are righteously indignant. Or at least they would be if they even thought about it anymore. Most fans have long ago stopped worrying about this inherently unfair aspect of football.

If you enjoyed this post, you might find value in my Guide to Football for the Curious. Get a copy here!

Thanks for the question,

Ezra Fischer