Dear Sports Fan,

How do punts work in football?

Thanks,

Sara

— — —

Dear Sara,

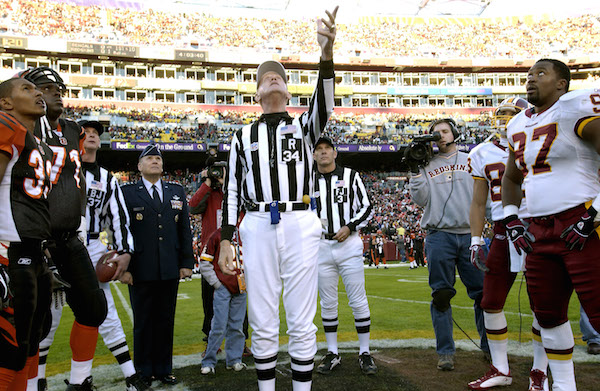

The punt is a unique and important play in football. Punting is the most common way that possession moves from one team to the other. As such, it’s a transitional moment, and like many transitional moments, it’s fascinating because it has so many different possible outcomes.

To understand the punt, it’s important to have a quick refresher on how downs work in football. In the National Football League, whenever a team has the ball, they have four downs or attempts to move the ball ten yards. Thus, first down and ten means they are on their first chance of four to move the ball ten yards. If they run the ball two yards on their first try, the next down will be called second down and eight (to go). If they try four times and don’t travel ten yards, the other team will get the ball wherever the first team had it when they failed to get those last yards. Instead of allowing that to happen, a team can (and often does) choose to kick the ball. If they are close enough to their opponent’s end-zone, teams will usually try a field goal (kick the ball between the uprights, get three points.) If not, they usually make the decision to punt the ball.

When a team lines up on fourth down to punt the ball, instead of a quarterback behind the center, there’s a specialist player called the punter back there. Being a punter in the NFL is pretty awesome. Last year, punters in the NFL made between $495,000 and $3,250,000! It’s a nice job, but there are only 32 of them around. Punters don’t have quite the pressure on them that field goal kickers do but, like their field goal kicking brethren, they rarely get hit. The punters job is to stand about fifteen yards behind the line of scrimmage, catch the snap that comes spiraling back to him, and then punt the ball.

Lots of things can happen once a team begins to punt:

- If it goes out of bounds, the team that didn’t punt (the receiving team) gets the ball wherever it left the field, no matter how high above the ground it was.

- If the ball lands on the field and no one from the receiving team touches it, the punting team will race down the field and touch the football. The receiving team gets the ball wherever the punting team first touches it.

- If the punt lands in the end-zone or goes out the back of the end-zone, it is a touchback and the receiving team gets the ball on the twenty yard line.

- If a player from the receiving team catches the punt (or picks it up from the ground) he can run with the football. Wherever he gets tackled or goes out of bounds is where the receiving team gets to start with the ball. Normal rules apply to this runner, so if the kicking team can knock the ball out of his hands, that’s a fumble and fair game for anyone to pick up.

- If someone on the receiving team tries to catch the ball but he flubs it and it falls to the ground, or if the punt just bounces off anyone from the receiving team, then the kicking team can grab the ball and they get it back for their offense! There’s usually a wild free-for-all when this happens.

- Because it’s potentially pretty dangerous to be looking up in the air to catch a punt while players from the kicking team are sprinting at you trying to hit you as hard as they can, the player from the receiving team who is tasked with catching the ball can call a Fair Catch by waving their hand up in the air before catching the punt. If they call a fair catch, the opposing team is not allowed to hit them but they cannot run with the ball either. The receiving team gets the ball wherever it is caught.

- The punt can be blocked by the receiving team before it gets going. When this happens, there’s a scramble to grab the ball. If the receiving team, which blocked the ball, gets it first, they can run with it as far as they can. If the kicking team gets it, they give up possession wherever they get control of the ball. In the odd case that the kicking team catches the blocked punt before it hits the ground, they can run with it!

Football is all about technicalities, isn’t it? They’re more fun when you understand them. Tomorrow, we’ll take a look at how punts can be exciting for each team.

Thanks for your question,

Ezra Fischer