Errol Morris is widely regarded as the premiere documentary filmmaker alive. This week, the sports and culture website Grantland has declared it to be “Errol Morris” week and is celebrating their own invented holiday by releasing a brand new Errol Morris short documentary each day. The first one, It’s Not Crazy, It’s Sports: ‘The Subterranean Stadium’, is a 22 minute slice of life focusing on a man whose love for electric football permeates the life of his wife, family, and friends. I plan to watch and review all of the films this week. For full disclosure, I am a big fan of both Grantland and Morris, so I’m likely to enjoy most of them. I loved this one.

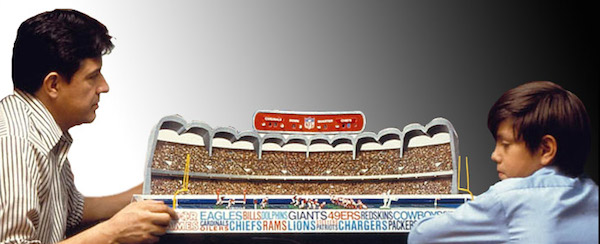

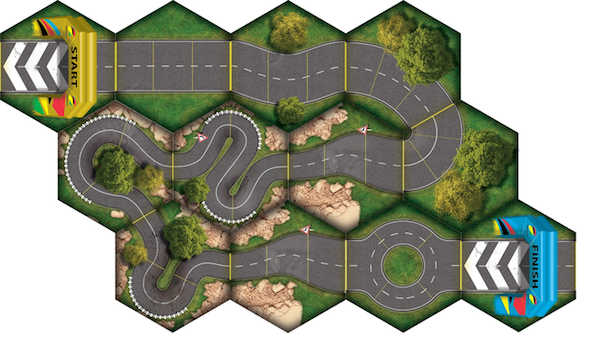

The film begins by focusing on the game of electric football. Electric football is a table-top game invented in the late 1940s and still produced today. Although its prominence in the world of football make-believe and simulation has long been superseded by both fantasy football and football video games, electric football continues to have a passionate following and is still sold today. Since its invention, more than 40 million sets have been sold. Players set up miniature football players on an electrified field. When a switch is flipped, the field electrifies, and the players, whose bases serve as conductors (both for electricity and to provide direction for the player), take off. When a defender makes contact with the player with the ball, the play is over and the setup begins again. By now, of course, you might be thinking that you don’t actually feel that interested in the minutiae of an archaic sports simulation. You’re in luck. No matter what the subjects of Morris’ films are, what he cares about is people.

People are the true focus of this film and the results are spectacular. Morris’ films can be separated into two main groups: the ones where he takes a serious topic and dissects it (like wrongful conviction in The Thin Blue Line, the Vietnam war in The Fog of War

, or Abu Gharaib in Standard Operating Procedure

) and the ones where he takes a frivolous or mundane topic and enlivens it (like small town life in Vernon, Florida

or animal lovers in Gates of Heaven

). This is definitely an example of the second. Love and humor are present in the thirty year tradition of gathering once a week in John DiCarlo’s basement to play electric football but as the documentary goes on, you begin to understand that there’s real pathos as well. Morris and whoever created the music for the film do a masterful job of allowing some of the tough realities of these people’s lives trickle into the film. You learn that DiCarlo is a Vietnam veteran who suffers from serious health problems due to his exposure to Agent Orange. The scene-stealing star of the film, a hot-blooded hot-dog vendor nicknamed Hotman (real name Peter Dietz) provides laughs and grins for most of the film and then the best line towards the end. When discussing his regret about never having children, he looks at the camera and says, “I had to play the hand I dealt myself.”

“I had to play the hand I dealt myself.” That line perfectly encapsulates this short film. The people who congregate in John DiCarlo’s Subterranean Stadium are realistic about their lives but also unrepentant. They know better than we do that winning an electric football simulation can only momentarily sooth the wounds of the lives they’ve lived, full of war and drugs and hardship and loss, but they’re unrepentant. The awkward beauty of the mangled card metaphor is that, had Dietz thought about it a little longer, he would have found that the perfect metaphor wasn’t playing cards with all its inherent randomness but electric football where you place the players where you want them and then sit back and watch the action unfold.