Dear Sports Fan,

Why do cyclists in the Tour de France bother going out on breakaways? They always get caught!! What is the point?

Thanks,

Lester

Dear Lester,

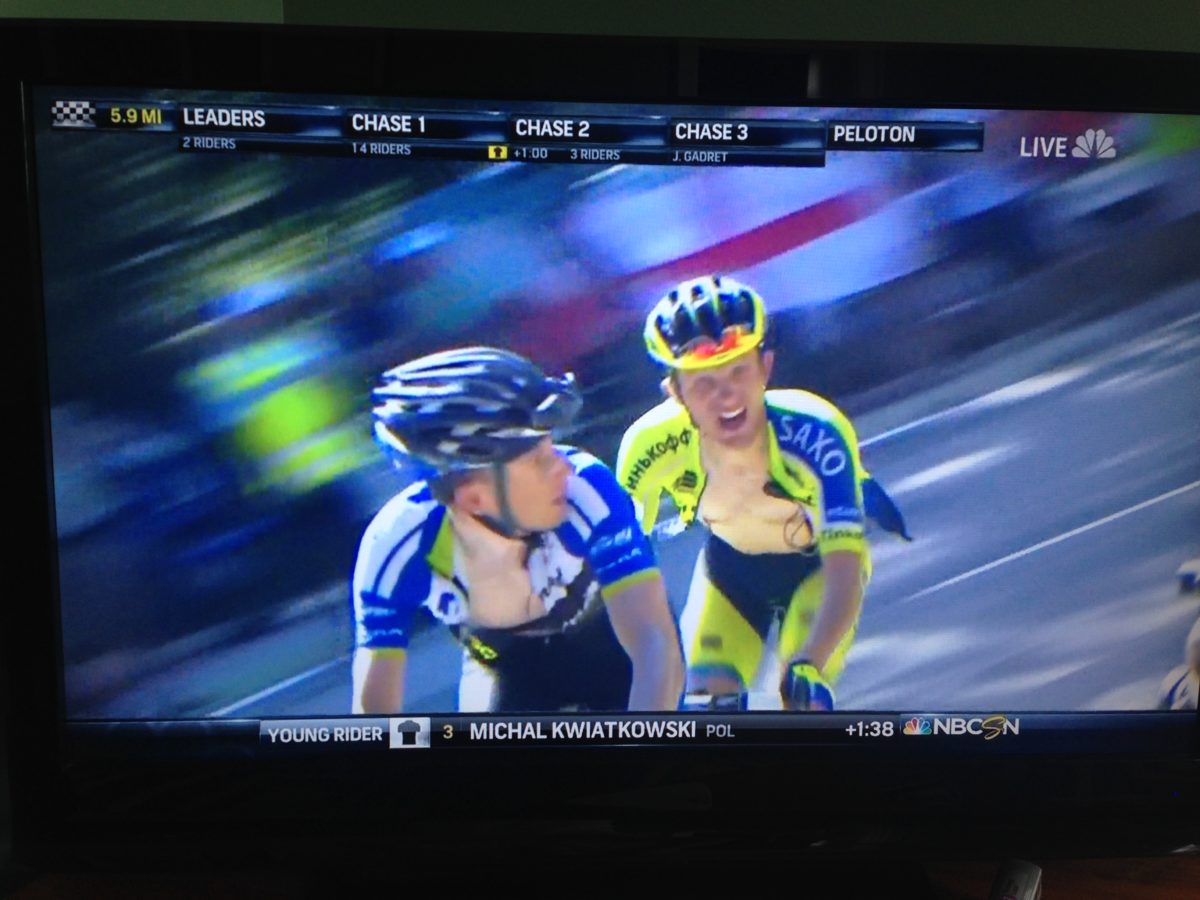

It’s one of the most common and most heartbreaking sights of the Tour de France — a small group of riders, or even a single rider, have led the race for fifty miles or more, over mountains and through valleys, across bridges and through forests. Then, with the finish line metaphorically or sometimes even literally in sight, they are caught by the big pack of riders called the peloton. How does the peloton always seem to catch them at just the right time? Why can they go faster than the breakaway? And, as you put it, why bother going out on breakaways if you’re always going to get caught?

First they physics of it — the peloton is always able to go faster than a single rider or small group of riders because they have more riders to rotate through the painful position of being at the head of the pack. The person in front “breaks the wind” for all the riders behind them. This is an exhausting position, and even the superhuman (implication intended) athletes of the Tour de France can only do it at full effort for so long. In a solo breakaway, a rider must always fight the wind, in a small breakaway, even when the riders cooperate, each person’s share of the effort is bigger than in the peloton. Race radios, allowing team coaches to communicate with the riders on the course, help the peloton time its effort so that it catches the breakaway at just the right moment.

Luckily for viewers of the Tour, there are still a bunch of legitimate reasons for cyclists to go out on breakaways. A tour with nothing but a single pack of riders would make for boring viewing!

Like in many European sports, there is more than just one prize to shoot for in the Tour. Aside from the yellow jersey, which goes to the rider that completes the stage and eventually the race in the least amount of time, there are two other cumulative jerseys to race for. The green jersey goes to the best sprinter in the race and the red polka-dot jersey on a white background goes to the King of the Mountains. In order to win either of these jerseys (and the money that comes along with the prestige) you have to accrue the largest number of mountain or sprint points during the tour. Although many of the biggest sprints (and a few of the biggest mountain summits) are at the end of stages, most of them are intermediate or during the race. A rider in a breakaway has a good shot at winning an intermediate sprint or being the first over a summit. This helps if they are in contention for the green jersey or the King of the Mountain competition or it can help a teammate of theirs if it denies someone on another team those points. And, these intermediate sprints and summits come with cash prizes.

A third, less visible secondary prize may even be more directly affected by participating in a valiant but eventually unsuccessful breakaway — the Combativity Award. Unlike all the other competitions we’ve discussed before, this award is subjective. A panel of judges watches and votes on the rider for each stage and for the tour as a whole (the one for the tour as a whole is called the “super-combativity award… I’m guessing there may be some slight transliteration issues here…) who is most aggressive. Although this award does not come with a jersey, it does come with cash and some amount of notice in the cycling world.

If you’ve been watching the Tour, you no doubt noticed that each rider wears a jersey with their team’s sponsor emblazoned all over it. The brand name of the sponsor IS the team name. It’s not the “Amazon Bowstrings,” it’s just “Amazon.” Although this may feel foreign to American sports fans who quiver just at the thought of putting an advertisement on their favorite team’s jersey, it’s an integral part of cycling. A rider who can make it into a small group at the head of the race and stay there for three or four hours has successfully captured free advertising for their sponsor for the same amount of time on television. And that rider knows the team sponsor will notice it and remember when the time comes to renew contracts.

So far we’ve been describing only rationales for taking part in a breakaway that don’t have to do with winning the race, either that day or the whole tour. Well, here’s a tactical reason that does have to do with winning. A team that has a rider in contention for winning the whole race (called general classification or GC) may sometimes want to hide one or two of that rider’s teammates in a doomed breakaway. That way, if the GC rider feels like they have an edge on some of their GC competitors and is able to break away from the peleton, they will have teammates ahead of them who can fall back and help their GC teammate extend his lead over the other GC riders.

If all of these reasons are still not good enough, there is this: sometimes it does work. Sometimes the peloton, even with the advantage of physics and race radios, mis-times their charge and can’t catch up in time. Or, sometimes the team tacticians may decide it’s simply not worth expending the energy to catch the breakaway. Cycling is a relatively predictable sport after the first five to ten riders. If no one in the breakaway group is in the top ten, they probably pose no threat to the GC riders who feel they have a chance at winning the whole race. So, those GC riders and their teams may decide it’s more important to save their energy or try to make a late move on another GC rider than to organize the peloton for a long chase.

Thanks for reading,

Ezra Fischer