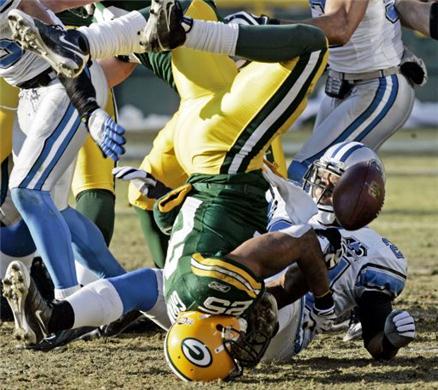

The National Football League has a complicated problem. It’s becoming increasingly clear that the league will disappear into oblivion if it can’t find a way to change its product so that football stops killing its workforce without ruining its entertainment value. My favorite simple solution is to reduce the roster size of football teams. From the 53 active players a team is allowed today, I propose reducing the number to 20. This single change will make football a safer and more interesting sport. Think of it as one small step for a rules committee but one giant step for football.

In four posts over the last week, we’ve established the need for football to evolve and explained some of the important factors that constrain how this can be done. Brain injuries are a serious problem for the long term health of football players, whether in the form of concussions or subconcussive injuries. We also know how and when brain injuries happen during a football game. The majority of subconcussive impacts happen in the clash between offensive linemen and defensive linemen, and that concussions are caused primarily when players collide at great speed or can’t prepare themselves for a collision. We chronicled football’s long history of changing rules to protect players from the most violent forms of physical contact, and we discovered that these rules largely made the game more dangerous in terms of concussions by allowing players greater freedom to speed up before hitting or being hit by an opponent. While we are unlikely to take back rules that protect football players’ knees, shoulders, and faces, it is hard to imagine further restricting the game by layering on another set of rules for preventing brain injuries. If football continues on without addressing these problems, it risks having no future at all. If we’re going to fix football, we need to think bigger than that. Or, as it may be in my suggestion, smaller.

Reduce the roster size? Why?

There’s a saying in football, “Speed kills.” In a tactical sense, this phrase means that a fast player, usually a wide receiver or running back on offense, can ruin even the best defensive plan and win a game for his team. What’s also true is that speed is the primary factor in the potentially widespread brain injuries that threaten the future of football. The speed of the game is why wide receivers and defensive backs have no time to brace themselves before they collide and why they are the two most commonly concussed positions. It’s why players can’t avoid kneeing their teammates in the back of the head as they run by. Speed kills.

Speed, not simple physicality, is the reason that football has the highest incidence of concussions of all sports. If it were simply a question of how physical a sport is, then wrestling would top the list. If we could magically slow football down, like a record on a turntable, we could keep the sport we love and rid it of the cancer tearing it apart from within. The easiest way to make football safer is to slow it down.

The problem is: how can you slow football down? I’m not the only one to ask this question. Malcolm Gladwell asked it in his landmark 2009 New Yorker article on this topic: “But how do you insure, in a game like football, that a player is never taken by surprise?” In considering this problem, I asked myself,”What is the biggest factor contributing to football’s speed?”

The reason why football is such a fast game is because its players are able to go at full speed almost all the time. Football players are underutilized. That is, football has less active time than other sports. Active play also takes up a smaller percentage of game time than other sports. Football has larger rosters than other sports and players play a dramatically lower percentage of the game than athletes in other sports. We’ll go into all of this in some detail below. As a result, football players are able to get to full speed and power on every play. They explode off the line of scrimmage, they launch themselves into tackles, they churn their legs, grinding out every inch of every play.

In addition to having the energy to go all out on every play, football’s luxurious roster size gives players the ability to become highly specialized. Players who play offense do not play defense. Players who play offensive line do not run with the ball or catch passes. Players who play cornerback would be lost if asked to play even a position as similar as safety. Teams have players who play defensive end basically only when they know the other team is going to pass. Teams have slot receivers and outside receivers, blocking tight ends and receiving tight ends. Each role on a football team favors a particular body type. It doesn’t mean that they can’t be done by an unusually shaped person, but there is an ideal.

In his brilliant book, The Sports Gene , David Epstein writes about the “big bang of bodies” that occurred in the mid-20th century. As sports leagues became simultaneously more accessible to people of different backgrounds (both non-North Americans and people of color) and exponentially more financially rewarding to players, the diversity of body types across all athletes grew and the specialization of body types in particular sports or positions rocketed. Nowhere is this more obvious than in football, where the average running back today is 5’11” and 215 pounds while the average tackle on the offensive line is 6’5” and 313 pounds.

, David Epstein writes about the “big bang of bodies” that occurred in the mid-20th century. As sports leagues became simultaneously more accessible to people of different backgrounds (both non-North Americans and people of color) and exponentially more financially rewarding to players, the diversity of body types across all athletes grew and the specialization of body types in particular sports or positions rocketed. Nowhere is this more obvious than in football, where the average running back today is 5’11” and 215 pounds while the average tackle on the offensive line is 6’5” and 313 pounds.

With few exceptions, specialization has meant increasingly enormous players. Craig M. Booth tracked player weight by position back to the 1950s and created a set of wonderful charts to visualize the changes. The increase in size over time, especially among the largest players on the field, the offensive and defensive linemen, is remarkable. Hall of Fame quarterback Fran Tarkenton wrote about this in a piece for the Wall Street Journal in 2013: “When I entered pro football in 1961, every member of my offensive line weighed less than 250 pounds. In my last year, 1978, our biggest linemen were only around 260 pounds. No Super Bowl-winning team had a 300-pounder on its roster until the 1982 Washington Redskins. Now it is unusual for a team to have fewer than 10 300-pounders.“

Tarkenton speculates that the increase in size is due to the use of performance-enhancing drugs. It’s certainly possible, and stronger enforcement of existing rules against performance-enhancing drugs would be a good thing. Whether or not drugs are involved in helping players bulk up, it’s football’s specialization that enables them to succeed at that size. Ben McGrath, writing for the New Yorker about the future of football agrees: “with specialization came increased speed and intensity, owing, in part, to reduced fatigue among the players, as well as skill sets and body types suited to particular facets of the game.”

The best way, perhaps the only way, to slow football down is to tire out its players. Reducing roster sizes will force players to play more, which will make them play at a slower pace. As a bonus, it will encourage them to train for endurance, lowering their weight and therefore the power they have to hit each other. Even a marginally slower football would be much safer. Remember, these are elite athletes with incredible reflexes. Give them an extra few tenths of a second to see a hit coming and to prepare for it and they can usually prevent a concussion.

A great part about this evolution of football is that it will make the game more interesting to follow. That may seem like small potatoes next to making it safer for its players and by doing so, ensuring the sport’s continued existence, but it’s something almost no other solution can claim. Let’s theorize about the effect of reducing NFL rosters from 46 to 20.

How would reducing roster size change football?

20 still seems like a lot of players, especially if only 11 are needed on the field at one time. It’s two short of twice the number of players you would need if you wanted everyone to play only on offense or only on defense and if you ignored special teams plays and never wanted to have the flexibility to use different formations on offense or defense. I imagine in reality, this is roughly how rosters would break down.

- 2 quarterbacks (probably still specialists)

- 7 little guys – wide receivers and running backs who also play defensive back

- 7 big guys – offensive linemen and defensive linemen

- 3 medium guys – linebackers or hybrid offensive players, a little like Charles Clay or Marcel Reece today on the Miami Dolphins and Oakland Raiders who play a little fullback, running back, and tight end.

- 1 kicker/punter

Of the 20 players on the roster, 17 might regularly play both sides of the ball. That’s a big change! It would mean more than doubling the number of plays per game for most NFL players. How would teams react?

Luckily for us, we do have some clue about what would happen. College football is a great experimental sandbox for the NFL. Players in college are smaller and slower than NFL players and because of that, a wider range of strategies is tried and proven successful. Mike Leach is one of the most extreme football scientists who experiment in college football. When he came to national attention in the mid-2000s, Leach was head coach of Texas Tech. His approach to football offense was to raise the tempo of the game until his team was regularly running around twice the number of plays compared to a normal offense; and twice the number of plays that a normal defense was prepared to play in a single game.

In 2005, Michael Lewis wrote an article about Leach for the New York Times magazine and described what happened to the Texas A&M defense when they were forced to defend Texas Tech’s high tempo offense:

The A.& M. front line appeared tired. “The minute you see the defensive line bent over and their hands on their hips,” Hodges told me, “that’s when you know you have them.” The A.& M. linemen were a lot bigger than the Texas Tech linemen. They may or may not have been fatter – Leach insists they were – but their bodies were clearly designed for a different sort of football game than this frenetic one. “That’s the risk of playing 330-pound guys,” Leach said later. “You get good push, but if you got to run around a lot, you get tired.” Before the game, Leach had said to Hodges: “Get those fat guys up front and make them run. They’re already a little slow. By play 40, they’ll be immobilized.” That was one reason he kept sending so many receivers on deep routes: to force the defense to run with them.

Teams like Texas A&M never had an incentive to change the makeup of their roster because they only played at Leach’s pace once a year and against teams their own size the rest of the time. If NFL rosters were cut to 20, teams would have to adjust. A 6’5” 330-pound man can only play so hard and so fast for so long.

There’s no way that I can accurately predict what hundreds of coaches, all working overtime on figuring out the best way to win given the new realities of the sport, would come up with, but I believe these are some likely tactical outcomes:

- Teams would choose to hire smaller players. The average size of players, particularly offensive linemen, defensive linemen, and linebackers, would come down significantly. 330-pound players would become obsolete and 300-pound players would be relatively rare. Not only would this be because of the greater aerobic demands of the game but also because smaller rosters will reward versatility. In a pinch caused by injured teammates, players will need to be able to play many positions.

- Most teams would play at a slower tempo. On average, the time between plays would go up as players leverage the full play clocks to catch their breath.

- A few teams would sell out on a high tempo offense, roster even smaller players who can run all day, and try to do what Mike Leach did to Texas A&M.

- Regardless of tempo, players will be significantly slower. They’re more likely to be fatigued in-game. Just that factor will slow them down as they conserve their energy for the fourth quarter. Also, because of the increased demand on their endurance, they will train more for that and less for explosiveness. Football players will carry less fast-twitch muscle and much less fat.

- Players would enter games carrying preexisting injures much less frequently. It’s harder to play through pain when you’re playing twice the number of plays and it’s more risky for a team to bring an injured player into a game when it has so many fewer available substitutions if he cannot finish the game.

- A greater number of strategies would be used by teams. By encouraging smaller players and slowing the game down just a bit, the field will effectively expand. Tactics like running an option offense, which work today in college football but not the NFL because players in the NFL are too big and fast, will work better in this future NFL. This will make coaches who are great strategists even more important than they are today.

The simple rule change and its likely strategic adjustments will single-handedly make football safer. It will reduce the effect of subconcussive brain injuries as well as concussions.

Is football really less active than other sports?

We think of football as one of the toughest, most physically demanding sports out there. In some ways, this is true. There is no doubt that football players are incredible athletes. Football players run faster, hit harder, and catch better than any other athletes. They endure more spectacular impacts than people in most other sports as well. It’s also true that football players play through injuries that would leave players in other sports sidelined for days and normal people laid up for weeks. In one particular set of ways, though, football is surprising in how little it demands from its players. Football players don’t have to play very much football. It’s this factor that reducing football’s roster size would counteract. Although it sounds dramatic, the figures that follow will show how doing this would be bringing football closer to other sports. What’s actually dramatic is how much of an outlier football is today.

Football has the shortest season of all American professional sports by far: only 16 games. Compared to Major Leagues Soccer’s 34, the National Basketball Association and National Hockey League’s 82 or Major League Baseball’s astounding 162, 16 is a tiny figure. Football players expect to play once a week for around 20 weeks. Players of other sports play several times a week over a longer period.

Football is not the shortest game in terms of game time but look beyond the clock and you see another story. If you focus only on the time that players are actively playing, football has by far the least actual play time. An NFL game is said to have just 11 minutes of action within the 60 minutes of game time. Soccer games are estimated to have 68 minutes of action out of 90 (yes, make your zero minutes of action joke now). I wasn’t able to find a stat for basketball or hockey but because their official clocks stop whenever there is a whistle, it’s safe to assume that they are close to 100% active.

The chart below shows that football players play less and do it over a longer time than players in other major sports. To show this in a single metric I divided the amount of active time during each sport by the amount of real time from the start of a game to the end. As you can see, football players are active only 6% of that time. This is far less than other sports.

| Pro Sport |

Game Time |

Real Time |

Active Time |

Percent Active |

| Football |

60 min |

190 min |

11 min |

6% |

| Soccer |

90 min |

105 min |

68 min |

65% |

| Basketball |

48 min |

138 min |

NA (Assume 100%) |

35% |

| Hockey |

60 min |

139 min |

NA (Assume 100%) |

43% |

One would be forgiven for thinking that this relative idleness makes football safer. If football is dangerous, this line of thought would say, then how can playing less of it make it more dangerous? The problem is that the less active players are during a game, the more they are able to exert themselves when they are active. A football player, playing only 6% of the time over more than three hours can exert themselves to the fullest on every play. They can go full speed and as we already discussed, speed kills.

Even six percent is actually a gross overstatement of how active a football player is during a game. Football is divided into three phases: offense, defense, and special teams. Offensive players virtually never play on defense, defensive players almost never play on offense, and special teams (for kickoffs, field goals, and punts) often are a separate group of players. At most, an offensive or defensive player will be active not for 11 minutes but for around four minutes and 40 seconds, but even that overstates how much active playing time players get because most players don’t play all the plays, even in their phase of the game. Football is a game of specialist players who are deployed when the situation calls for their skills.

Football’s specialization is made possible by the deep rosters of football teams. Football teams have the largest rosters of any sport. For every football game, a team can have 46 players on the sidelines, in pads and helmets, ready to step onto the field when needed. That’s close to double the sport with the next largest roster! Let’s see how it compares to other sports:

| Pro Sport |

Players on Field |

Players Available |

Percent Utilized |

| NFL Football |

11 |

46 |

24% |

| NHL Hockey |

6 |

20 |

30% |

| NBA Basketball |

5 |

13 |

38% |

| MLB Baseball |

9 |

25 |

36% |

| English Premier League Soccer |

11 |

25 |

44% |

As you can see, the numerical discrepancy in utilization is not as large as it is with active playing time but it is still noticeable. College football is even worse, with rosters varying from 60 to 105 players, all eligible to play in a single game! Realistically, there are factors in other sports that artificially lower their utilization numbers. Common wisdom in the NBA says that a winning team cannot have more than a seven or eight-man rotation, nine at most. NBA teams carry 13 players but a handful of players play very little. Baseball’s roster includes a rotation of starting pitchers that only play once every five games and relief pitchers who play only small portions of games. Soccer has limited substitution rules that limit a team to three substitutions per game. So while 25 players are eligible to play in each game, only 14 may actually do so. If we take those factors into consideration, the table looks more like this:

| Sport |

Players on Field |

Players Available |

Percent Utilized |

| NFL Football |

11 |

46 |

24% |

| NHL |

6 |

20 |

30% |

| NBA |

5 |

9 |

55% |

| MLB (position players) |

8 |

13 |

62% |

| EPL |

11 |

14 |

79% |

Hockey is the only sport close to the NFL in terms of player utilization. Hockey players, who play between one third and one half of the game in 40-second to one-minute spurts, are the second most underutilized athletes. It’s no surprise that hockey’s brain injury crisis rivals football’s.

Is this the perfect solution?

This isn’t a perfect solution. For one thing, it’s almost impossible to imagine it happening. Despite being a safety measure intended to protect football players, it would also result in the loss of three fifths of the current NFL jobs. That’s a problem! Not only would it violate the terms of the current collectively bargained agreement between the NFL and the NFL Players Association but it’s pretty crazy to think any future Players Association would allow it. The truth is that a combination of factors will need to be in play to solve the concussion crisis. Here are some other things that should be considered.

- Fix the helmets. Whole essays could and have been written about just this topic but a brief summary is that football helmets have evolved to protect against cracked skulls and broken noses but not concussions. They are so good at doing the job that they were designed to do that players use them as weapons. A lighter football helmet would help prevent concussions. Creating a football helmet with no face-mask or by removing them completely might teach football players to play in a safer way. This isn’t as crazy as it sounds, one college football team is already practicing without helmets.

- Increase the penalties for dangerous play. Football could adopt something like soccer’s yellow card/red card or hockey’s power play. Both of these systems promote safer play by disproportionately penalizing the team of players who break the rules. One hockey executive also proposed fining coaches and team owners in addition to players for unsafe play.

- Add limited substitution rules. The sport that does this today is soccer. Although soccer teams carry 25 players, they are only allowed to substitute three times during a game. The benefit of this would be that you could preserve more jobs for football players while having the same effect on the speed of the game. The downside is that, like soccer is facing now, football would face the serious issue of an injured player staying in a game because his team has run out of substitutions and cannot replace him.

Although I hope football reduces its rosters to protect players from brain injuries, I’m not holding my breath. A more realistic hope is that medicine catches up to the demands of the sport. Progress is already being made. A recent study was able for the first time to find evidence of damage in the brains of living football players. Given time and the continued incentive to study this topic, we will develop tests that can diagnose signs of future debilitating problems early enough to prevent young football players from continuing to play until their brains are irrevocably damaged.

Still, a writer can dream, can’t he? In my dream world, the NFL doesn’t wait for scientists to figure this one out. Instead, they do what the leaders of their sport have been doing for over 100 years and change the rules of the game to improve the safety of its players. The simplest solution is to reduce teams’ rosters down from 46 to 20 players. This leaves football’s core rules the same and makes football more interesting to watch. By rewarding versatility and endurance, this single change would make players lighter and slightly slower. Asking football players to do more is not an intuitive way of protecting them, but it’s the best solution out there.

Here’s to saving football! To celebrate, I’ve invented a time machine, traveled three years into the future and made a copy of a Super Bowl preview from 2018 — the year after the NFL reduced its roster size to 20. Enjoy the game, both today and in the future.

Super Bowl Preview

Thursday February 1, 2018 • Minneapolis, Minnesota,

Roster construction is the overwhelming story leading up to Super Bowl LII between the New England Patriots and Philadelphia Eagles. The action on the field won’t begin until Sunday, February 4, 2018 at 6:30 p.m. ET but the games are already under way. The Super Bowl coaches don’t have to show their hands until the morning of the big game and both New England’s Bill Belichick and Philadelphia’s Chip Kelly are planning on using every minute of that time to perfect their strategies and keep the other side guessing.

We sent our best investigative football reporters to team practices this week but they came away with more questions than answers. Here are three of the hottest questions from each side of the big game.

New England Patriots

- Will the Patriots dress 6’5” 300 pound OT/NT Marcus Cannon or will they leave him out of the lineup and go small? The Eagles have been forcing their opponents to go small against them all season by not dressing anyone over 265 pounds. Belichick does not like to have the style of play dictated to him but it’s hard to imagine Cannon playing more than 15 or 20 plays if he is in the lineup.

- If New England dresses only four linemen, that’s a hint that they’ll be doing more of the flexbone/triple option plays that helped them get by the Oakland Raiders in the last round. The Patriots are fully capable of surprising us all but one would imagine that similarities between the Eagles and Raiders, who both go by the 2/7/7/4 rule would suggest a similar approach.

- Who will suit up at quarterback? Since Jimmy Garoppolo was injured in week 15, the Patriots have gone with a three-man rotation at QB: Cardale Jones, Julian Edelman, and Denard Robinson. Each QB/WR/RB has played in all of the Patriots playoff games and Belichick frequently mixes two or three qbs in the backfield simultaneously. After Robinson’s 4-7, 2 interception performance in the Conference Championship, there are rumors of a shortened rotation.

Philadelphia Eagles

- What chance does LeSean McCoy have to play this Sunday? He is said to be making good progress in recovering from the brain injury which he suffered making a game-saving tackle in the first round 34-32 victory over the Minnesota Vikings. Kelly is known for having very little appetite for dressing a player carrying even a slight injury but McCoy could be the rare exception. It’s hard to imagine a more important player for the Eagles than McCoy if he could play throughout the game.

- How long can starting quarterback and defensive end Colin Kaepernick hold up? Word from Eagles camp is that their closer, Philip Rivers, would be available as early as the third quarter, but it’s been ten weeks since the last time they asked the 36-year-old to begin his aerial assault earlier than the fourth quarter.

- Will the Eagles roster a kicker after missing out on three fourth down attempts that could easily have been converted to points? Head coach Chip Kelly and OC, Mike Leach, are known for their principled stand against kicking but is the Super Bowl really time to hold to principles? 6’, 193-lb Cody Parkey is not much of a field player but did make a couple of good plays at linebacker when pressed into service during the Eagles week six game against the Washington Warriors.