Dear Sports Fan,

I was watching a playoff basketball game last night and I heard the announcers talking about the game becoming a “two possession” game if someone made a free throw. It was clearly important but I’m not sure what it means. Is it about how much time is left? Or the score? What does it mean to be a two possession game? And why is it important?

Thanks,

Maria

Dear Maria,

A two possession game is a game in which one team is winning by enough points that the team that is trailing cannot catch up with a single score. The term is usually used in basketball and football, two games where scoring can be done in different increments. The number of possessions needed to tie the game is a simple mathematical equation based on how scoring works in each sport.

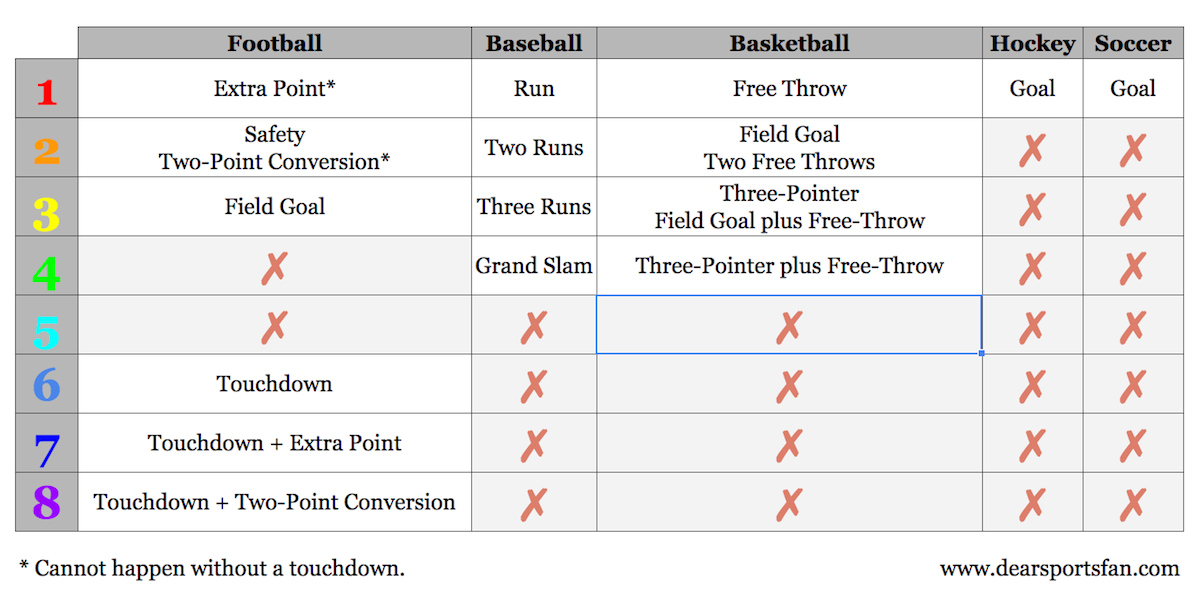

In football, the highest number of points that a team can score at a time is eight which they could achieve by scoring a touchdown followed by a two point conversion. A football game is said to be a “one possession” game if the team leading is leading by eight or fewer points. In basketball, the most points a team can score in one trip down the court is actually four points (a player is fouled while shooting a three point shot but still makes the basket; they are given the three points and get one chance at the free throw line to add a single point to their total) but this is so rare and so easy to prevent (just don’t foul a player taking a three point shot) that it’s generally discarded from the conversation. Instead, in basketball, a single possession game is generally thought of as one in which the team trailing is losing by three points or fewer. If you want more information (and a handy chart) on how scoring works across different sports, check out our post on the topic here. A two possession game in basketball is one in which a team is trailing by three to six points. Down by seven points? That’s a three possession game. 10, 11, or 12 would be a four possession game. Football follows the same pattern by eights. A zero to eight point deficit is a one possession game, nine to 16 is a two possession game, 17-24 is a three possession game, and so on.

The importance of whether a game is a one, two, or three possession game is tactical. While you were wrong in thinking that the term was based on the amount of time left, you were on to something. People usually talk about how many possessions apart the teams are only close to the end of the game, and end of game tactics are very much about the combination of score and time. A trailing team’s players, coaches, and fans are constantly doing a mental calculation: “how far behind are we and how much time do we have left to catch up?” One very useful short-hand to that mental math is to express both sides of the equation in terms of possessions — “how many possessions do we need to tie the game and how many possessions might there be time for?”

The end of basketball games is often defined by one team intentionally fouling the other. This topic is worth a blog post of its own, but the short story for why they do this is that a foul stops the clock. While fouling will give the other team an easy opportunity to get up to two points by successfully shooting free throws, it also extends the game by creating time for more possessions with the ball, during which the trailing team could score two or three points. What you probably saw was a player from the team that had the lead shooting a free throw that was intentionally given up by the trailing team. If that player had missed, the trailing team could have taken the ball and tied the game on that possession, whit a single shot. If the player made the free throw, it would have pushed the difference between the teams from three to four points, and meant that the trailing team would have needed to get the ball, score, and then either stop the other team from scoring or intentionally foul again, before having a chance to tie the game. The difference between a one possession game and a two possession game is a big deal.

Thanks for reading,

Ezra Fischer