Dear Sports Fan,

What is a set play in soccer?

Thanks,

Kimberly

Dear Kimberly,

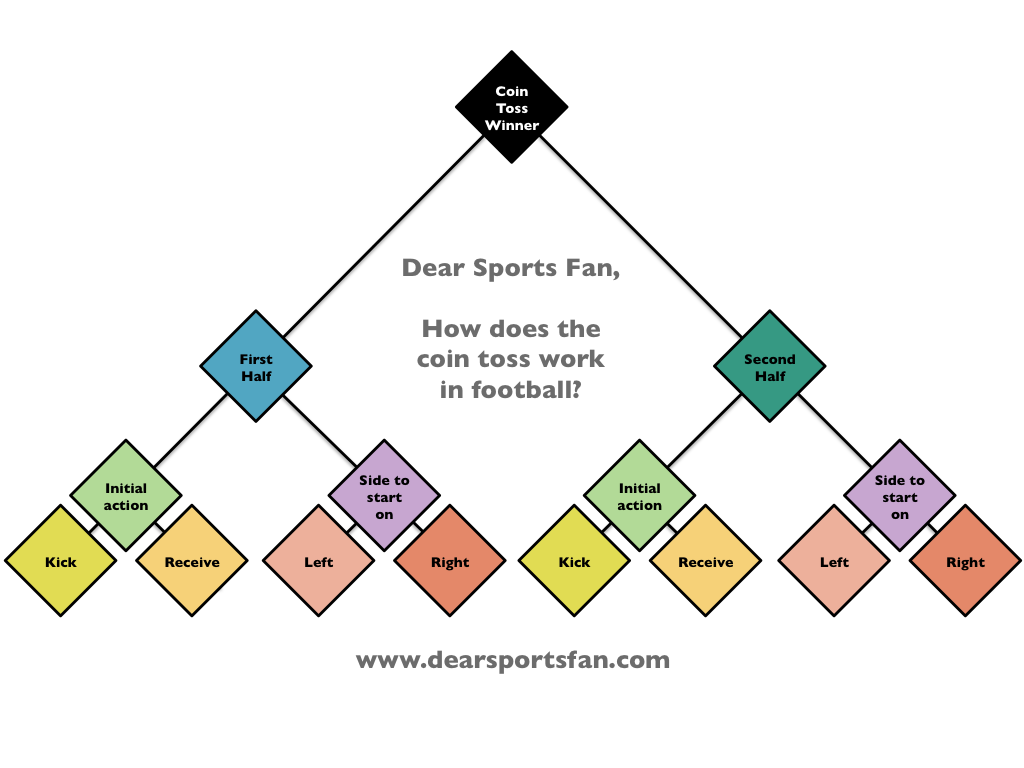

A set piece in soccer is any play that begins with the ball at a standstill following a stoppage resulting from the ball going out of bounds or a foul being called. Set pieces or set plays are unique in soccer because they are the only times when the ball is in the complete possession of one team, without the other team being allowed to try to get it from them. The team with the ball has all the time they want, within reason, to set themselves up in whatever position or formation they want before they put the ball back into play. Set pieces are much rarer in soccer than in other sports. American football is on the other extreme end of the spectrum. Football has only set plays — everything stops and starts between each play. Baseball is the same way. Basketball approaches soccer’s fluidity but there are far more stoppages between plentiful baskets, fouls, and time-outs.

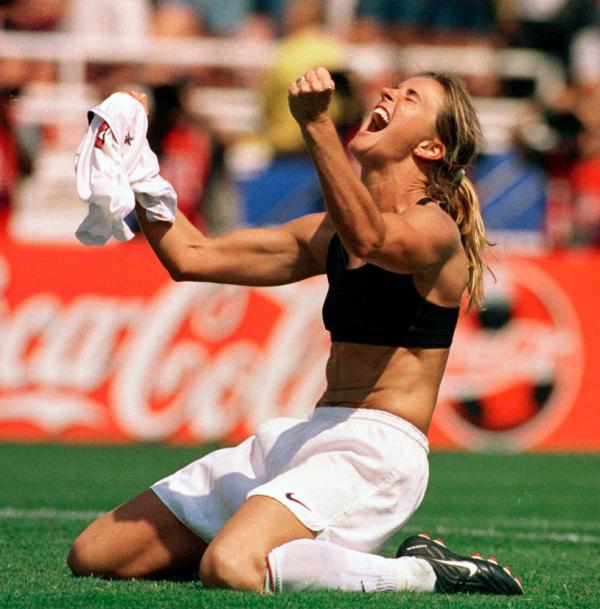

Set pieces in soccer are very valuable. Over the past five years or so, the percentage of goals scored during set plays in top-flight soccer has varied from around 25% to close to 50%. One quarter to one half of all goals scored in soccer are the result of set plays! In the 2014 World Cup, the championship team, Germany, averaged a set play goal per game, the highest in the tournament.

For something that’s so important, it’s surprising that there is such variation in how teams think about and practice set plays. Some teams practice them obsessively and even study how opposing teams try to defend them so they can use their opportunities even more effectively. Other teams look like they’re almost… well, winging them — playing them by ear. Trusting to the instincts and ideas of players on the field to figure out what to do with them as they come up. I have two potential theories for why this is.

The first is a cultural theory and it absolutely relies on gross national stereotypes, so it’s worth saying that I believe these tendencies are completely fluid and have absolutely nothing to do with anything integral to the people involved. For whatever reason, some national traditions of soccer are more focused on fluid play than others. English soccer is on one extreme — the English tend to play long ball, kicking the ball far in the air and then going up to get it. As such, the English are more likely to practice free kicks obsessively as an extension of their historic/cultural tendencies. The Brazilians are the opposite. They’re traditionally known for playing a fluid style based more on short passing, movement off the ball, and brilliant individual skill. Brazilian teams would stereotypically be less likely to spend time in practice working on set pieces because they are kind of the antithesis of how they like to play. Of course, just to make sure we don’t go too far overboard with this theory, we have the counter-example of the Brazilian fullback Roberto Carlos who was one of the best on set pieces ever:

I experienced a tiny microcosm of the cultural theory as a kid. My youth team was coached by a Guatemalan immigrant and we barely ever practiced set pieces. The teams we played against, particularly one run by a German-American group, had clearly practiced them a lot.

The second theory is that set pieces are a chance for less skilled teams to beat more skilled teams, so they are the ones that practice set pieces more. Keeping possession of the ball in a soccer game is all about talent. Creating a goal in the flow of the game is a challenge that can only be achieved with dominant skill or incredible luck. Set pieces, however, can be done with mostly precision and discipline. As The Guardian suggested in a 2009 article on this subject, there’s “a feeling that the top sides do not need to expend so much time and energy working on breaking down opponents through set-pieces when the goals tend to flow so easily from open play.” Whether it’s true or not, there’s a sense that practicing set pieces can only happen to the detriment of developing more important facets of the game. This is an argument sometimes used against how the United States develops soccer players.

Soccer has a variety of types of set pieces. Tomorrow, we’ll go into detail on each type of set piece: the corner kick, goal kick, free kick, and penalty kick.

Until then,

Ezra Fischer