Dear Sports Fan,

Why are sports teams from locations? I mean, it sounds like a silly question, but it’s not like the players or the coaches are from there. What’s the point of having a team from New York or Tennessee if you let people from all over play on it?

Thanks,

Jesse

Dear Jesse,

This is one of those questions that makes complete logical sense but, because it challenges a foundational aspect of the sports world in our country, is difficult for a fan to understand and answer. The fact that teams are tied to locations and that they represent the city, state, or region they’re from seems like an unassailable truth of sports. It’s not though. After doing some research on the topic, I’ve found an interesting example of one league that works completely differently. Let’s start with a little history, move on to the way things work now, and then look at an interesting exception that may be a harbinger of things to come.

From the very beginning of organized athletic competitions, sports have been a way for competing political groups to safely play out conflict. The ancient Olympics were dominated by individual events like running, boxing, wrestling, and chariot racing. Nonetheless, the competitors were there to represent the city-states they came from. Wikipedia’s article on the ancient Olympics states that the “Olympic Games were established in [a] political context and served as a venue for representatives of the city-states to peacefully compete against each other.” In the United Kingdom, some medieval soccer-like traditions survive and are still played. The Ashbourne game is a two-day epic played over 16 hours and two days each year that pits the Up’Ards against the Down’Ards. Instead of being the instantiation of a international or inter-city conflict, this game is a (at this point) relatively friendly version of a rivalry between city neighborhoods. There’s a natural human tendency to define oneself by splitting the world into “us” and “other” and where you live or where you come from is the obvious way to do this. Sports has always provided an outlet for group identity and simulated conflict.

Much of the early history of sport in the Americas is a history of college athletics. College sports, by their nature, are tied to a location and (however inappropriately) to an institution. The identification of teams with cities has also been present in American professional sports from the beginning. In baseball, the first professional team was the Cincinatti Red Stockings in 1869. The first professional hockey team was the Canadian Soo from Sault Ste. Marie in Ontario, Canada. Confusingly enough, the Canadian Soo played its first game in 1904 against the American Soo Indians from Sault Ste. Marie in Michigan, United States of America. Wha?? Football has an interesting professional history in the United States. For over forty years, there were professional players but no professional teams. Individual players were being paid to play on teams that were nominally amateur teams. It wasn’t until 1920 that the first professional football league came into being. The American Professional Football Association had teams from Akron, Buffalo, Muncie, Rochester, and Dayton. Basketball is a much newer professional sport. Its first game was played between teams representing Toronto and New York in 1946.

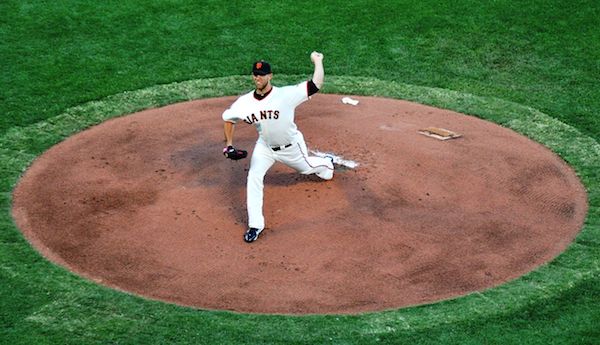

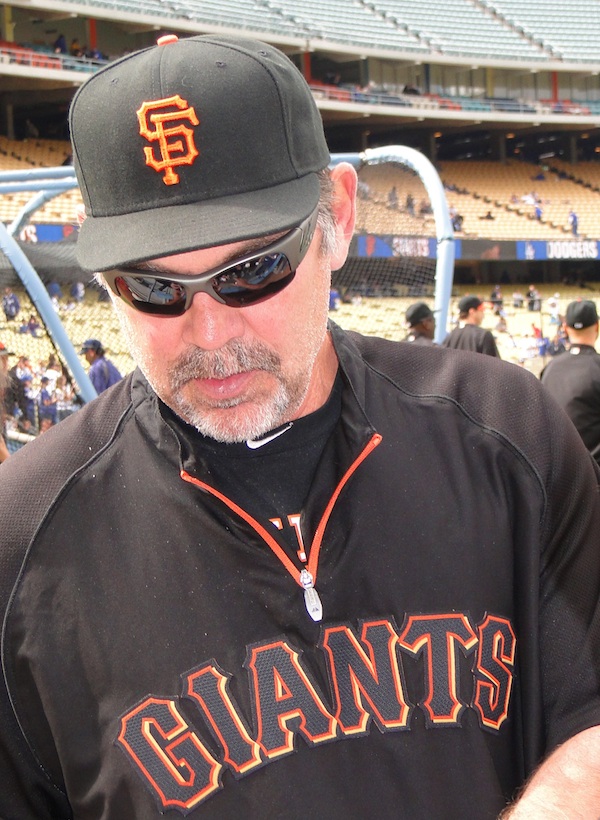

Even early on, teams were not made up of players from the team’s location. One reason is that some areas simply produce more top-level talent in some sports than others. It’s not financially smart for a league to only have teams in the core player producing areas, so instead, the players themselves travel and become ambassadors for spreading the game. For example, every single player on the 1940 Stanley Cup hockey champion New York Rangers team was from Canada. The 1949 Minneapolis Lakers may have had a slight over-representation of players who went to college in Minnesota with three, but the rest of their players went to schools around the country in California and Utah and Indiana. The famous 1972 Miami Dolphins, the only National Football League team to go undefeated throughout the regular season and playoffs, only had two Floridians in a roster of 50+ players. Aside from some areas just growing better athletes in some sports, the implementation of player drafts to balance the selection of players by professional teams and eventually free-agency to allow players some say in where they play serve to scatter players throughout the country.

As the big four American sports have spread throughout the world and our professional leagues have simultaneously gotten better at finding talented international players, the division of players from team location has become even more obvious. The NHL and NBA wouldn’t be half as good without players mostly from Europe, nor would Major League Baseball be as compelling without its (mostly) Central American and Japanese imports. While some teams have specialized in finding players from a particular region — think the 1990s Detroit Red Wings and Russia or the current Red Wings and Sweeden — international players have played anywhere and everywhere.

The idea of having teams made up of only players from the city or region they represent is a fun one and there are many counter-factual thought experiments around the internet in this vein. Yahoo recently posted a ranking of NBA teams if made up of only players from the team’s area. Max Preps published a map showing current NFL players by home state. It’s clear from the map that California, Florida, and Texas rule supreme, but I’d like to see the stats controlled by population to see which state is most efficient at producing NFL players. Quant Hockey has two interesting visuals about where NHL players come from. The first is a history of NHL players by home country, showing the increasing internationalization of the game and league. The second is an interactive map where you can look up the home towns of all your favorite (and least favorite for that matter) NHL players. The official NBA site has a similar map for NBA players. That the league itself bothered to put this together is an example of how important it feels the international nature of its sport is.

Sports teams aren’t all tied to locations. If we take a brief detour to the basketball crazy country of the Philippines, we find one of the most unique sports leagues out there, the Philippine Basketball Association. This league is made up of twelve teams. Team names are made up of three parts — a “company name, then [a] product, then a nickname – usually connected to the business of the company.” My favorite example is the six time champion Rain or Shine Elasto Painters owned by Asian Coatings Philippines, Inc. Teams are completely divorced from regional affiliation and play in whatever region the league rents for them to play in. This may seem like it’s completely crazy to those of us who are used to leagues in the United States, but it could be the future. Consider the increasing visibility of corporate sponsorships. In all leagues here, we have stadiums that are named after companies. The Los Angeles Lakers share the Staples Center with the Los Angeles Clippers and hockey’s Kings. The Carolina Panthers in the NFL play in the Bank of America Stadium. This isn’t a new fangled thing, remember that baseball’s historic stadium in Chicago, Wrigley field bears the name of the chewing gum its owner in the 1920s sold. The next likely step in the process is having corporate sponsorships show up on the jerseys of sports teams. This has already happened for most soccer leagues. Scott Allen wrote a nice history of this process for Mental Floss. The process has taken a long time, from the first corporate jersey in Uruguay in the 1950s to the final capitulation of the famous Barcelona football club in 2006. Allen provides several funny sponsorship stories, including my favorite, about the soccer team West Bromwich Albion:

From 1984 to 1986, the West Midlands Health Authority paid to have the universal No Smoking sign placed on the front of West Bromwich Albion’s jerseys. The campaign featured the slogan, “Be like Albion – kick the smoking habit.”

While the NBA, NFL, NHL, and MLB have resisted giving up their jerseys to their sponsors, speculation is out there that they soon will. Total Pro Sports has even designed a series of NBA jerseys with each team’s corporate sponsor on the front in anticipation.

Will the future be a complete takeover of teams from their old regional identities to new corporate ones? Or will we remain in an uneasy compromise between location and corporation?

We’ll find out together,

Ezra Fischer