Dear Sports Fan,

Are there rules for what color soccer goalies can wear?

Thanks,

Emma

Dear Emma,

FIFA, the international organization that coordinates soccer matches between countries and international tournaments like the World Cup, is rightfully getting a lot of flack these days for being unimaginably corrupt. They deserve every bit of the criticism they get and it’s okay to believe that and also take a second to marvel at the complexity of their task. They need to coordinate soccer games between 209 member associations, each with its own rules, customs, and yes, colors. Team colors and goalie colors are one small example of something which seems like it should be simple and indeed is based on simple principles, but which has a relatively complex set of rules that dictate how it works.

The principle that governs what color soccer goalies can wear is that they should be “clearly distinguishable from the Colours of the Playing Equipment worn by the outfield players of his own team, the outfield players of the opposing team, the goalkeeper of the opposing team and the Match Officials.” Goalies play by different rules than other players. Most obviously, they can use their hands to touch the ball within their own penalty box. It makes sense to want fans, other players, and the referee to be able to easily distinguish them from normal field players. Shirt color is a great way of doing that.

In practice this principle can be harder to meet than it seems. Shirt color is also the primary distinguishing factor in telling one team apart from its opponents and that is the first priority when it comes to choosing colors. In order to avoid a situation where both teams wear the same color, each team has a primary and secondary uniform. For example, Brazil plays primarily in a yellow jersey but also has a blue one for times when they play against teams like Colombia or the Ivory Coast which also use yellow as its primary color.

- Brazil: === | ===

- Colombia: === | ===

- Ivory Coast: === | ===

The matter of which team gets to play with their primary color and which team gives way is dealt with by always designating a “home” team even if a game is played in a neutral location. The home team always gets its choice of uniform. If they want to play with their primary uniform, which they usually will, the other team has to go to its secondary uniform. The reason why all of this is germane to a goalie’s uniform choices is that in order to wear a legal and distinguishing color, a goalie has to avoid the color of their team, the opponent’s team, the opponent’s goalie, and the referees, who also, it must be said, wear shirts. Using our teams above, this means that goalies in a game between Brazil and Colombia in Brazil could wear anything but yellow or red, but if it were in Colombia, they could wear anything but yellow and blue. If the Ivory Coast hosted Brazil, goalies couldn’t wear yellow or blue, but if Brazil was the home team, they wouldn’t be allowed to wear yellow or green. This complexity scales up and up when you consider a World Cup with 24 or 32 teams and the up to seven games against unknown opponents that teams have to be prepared for. And you think it’s difficult to pick out your clothes in the morning!!!

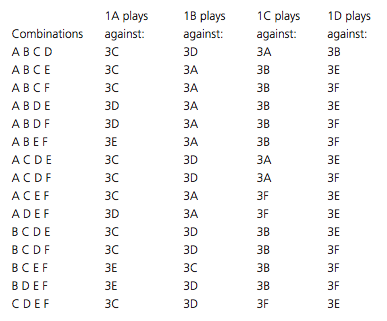

The way that FIFA handles this is by allowing/requiring goalies to have three different colored shirts prepared and registered before a tournament. For the 2015 women’s World Cup in Canada, here is how FIFA describes this requirement. “These three goalkeeper kits must be distinctly different and contrasting from each other as well as different and contrasting from the official and reserve team kits.” Basically, if you’re the goalie on Brazil’s team, you must have three colored jerseys that aren’t blue or yellow. This way, whether Brazil plays against Colombia at home or away, the two goalies combined will be guaranteed to have at least two shirts with color other than yellow, blue, and red. In the 2014 World Cup, referees had a choice of five different colors to help them stay away from any of the colors the teams and goalies might have chosen to wear.

It’s all very complex in theory and I’d love to see a mathematician model out how many different possible combinations there are, what the minimum number of options required is, and maybe even where the ideal contrasting colors fall on a color wheel. In reality, it’s easier than it seems to avoid non-contrasting colors for goalies because most countries stick to relatively mundane colors for their uniforms. There aren’t too many countries that stray from normal blues, reds, yellows, greens, blacks, and whites. A goalie could easily bring a single jersey that contrasts with every team in a World Cup if she’s willing to wear hot pink.

Thanks for your question,

Ezra Fischer

Emma asked me this question while watching a soccer game at the Dear Sports Fan Viewing Parties Meetup group. We’re open for new members! Join here.