Dear Sports Fan,

Why do sports leagues have All-Star games?

Thanks,

Greg

Dear Greg,

With the NBA All-Star game coming up soon, it’s a good time to tackle your question. All-Star games are an exhibition that many sports leagues put on in the middle of their seasons. Based on voting by fans, coaches, or some combination of the two, the best and most popular players are selected to play a game in mixed teams against each other. These games take many shapes and have different histories, but the common theme is that they generally lack the competitive nature typical of professional sports. They are essentially an entertainment, not a competition, and they are often accompanies by a host of other sports related competitions. All-Star games are loved by some fans, hated by others, and both loved and hated by a third group. They are more successful in some sports than others. So, why do sports leagues have All-Star games? Like any good child of children of the 1960s, my short answer is: follow the money.

From the start, All-Star games have been about money. The roots of today’s All-Star games can be found in games that were quite literally about money — benefit games. The NHL seems to have been on the forefront in this department. Wikipedia lists several early benefit games including a 1908 game to raise money for the family of a player who had drowned, a 1934 game to benefit a player who had his career (and almost life) ended in a violent hit, a 1937 game in honor of a player who had his leg shattered and died soon afterwards, and a 1939 game to benefit another drowned player. From raising money for a particular cause, All-Star games soon became about raising money directly or indirectly for the league itself.

Wikipedia tells us that the first professional league to have an All-Star game was Major League Baseball which held what they thought was going to be a one-time event in 1933 as part of Chicago’s World Fair. (quick side-note, if you haven’t read Erik Larson’s book about the fair, The Devil in the White City, you should!) History.com has a good article about the game, in which they claim that, “the event was designed to bolster the sport and improve its reputation during the darkest years of the Great Depression.” In the three years before the All-Star game, baseball’s attendance had dropped by “40 percent, while the average player’s salary fell by 25 percent.” Teams were experimenting with all sorts of promotions to try to bring fans and money back into the game and while Major League Baseball donated the proceeds of the All-Star game to charity, they surely profited indirectly from the attention it garnered. The All-Star game was a success, with hundreds of thousands of fans casting votes for which players they wanted to see and the top vote-getter, Babe Ruth, hitting a home run during the game. After the success of the 1933 game, baseball decided to make the All-Star game an annual tradition.

Other professional leagues in the United States soon followed along: the NFL in 1938, the NHL in 1947, and the NBA in 1951. For newer leagues, like Major League Soccer, the WNBA, and Major League Lacrosse, the inclusion of an All-Star game must have seemed like an obvious move. It seems like the All-Star game is primarily an American thing with some international sports leagues following along, but not all of them. The world’s most popular leagues — all soccer leagues, of course: the British Premier League, Spain’s La Liga, Germany’s Bundesliga, and the Italian Serie A don’t have All-Star games. The Canadian Football League had one on and off from the 1950s but has not had one since 1988.

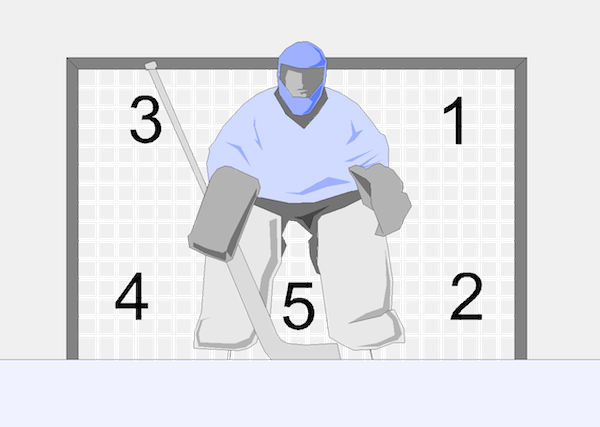

The format of All-Star games and accompanying competitive side-dishes have been tweaked over and over over the years to try to make the games slightly more competitive and therefore more entertaining to watch. These innovations seem to have generally moved in waves. Early on, some All-Star games were between last year’s championship team and a mixed team of players from other teams. After that, the now standard game between two mixed teams based on conference or league came into fashion. Two other formats that have been experimented with in the hopes of ginning up some competitive juices have been teams based on geographic origin (often the United States or North America vs. the rest of the world) or having teams chosen by two players or former players alternatively picking from the pool of All-Stars. I’m not sure that either of these have been very successful. The more successful though rare and extreme version of this is to actually invite a foreign team to play against a team made up of All-Stars. This happened very successfully in 1979 and 1987 in the NHL when teams of NHL All-Stars played against a Soviet national team. It’s hard to replicate that success because it was so reliant on the Cold War. Major League Soccer’s All-Star team plays against a European club team which kind of works but also is an admission of how weak the MLS is in comparison to other leagues. All of these innovations are intended to make the game more competitive. Perhaps the most extreme attempt came in 2003, when Major League Baseball took the extraordinary step of awarding home field advantage in the World Series to the league whose team won the All-Star game.

All-Star games are not only an opportunity for professional sports leagues to attract attention and earn money, they are also great opportunities for players. Players on the NBA All-Star teams this year will make $25,000 for playing in the game and another $25,000 if their team wins the game. The side-show events like the dunk contest and three point contest have their own purses that go to the individual winners of those competitions. Like for winning the Super Bowl, players may also have negotiated bonuses in their contracts for making the All-Star game.

The NBA All-Star game, which takes place this weekend in New York City, is definitely the biggest and most visible of the professional All-Star games in the United States. Check back in later today for a beginner’s guide to all of its elements.

Thanks for reading,

Ezra Fischer