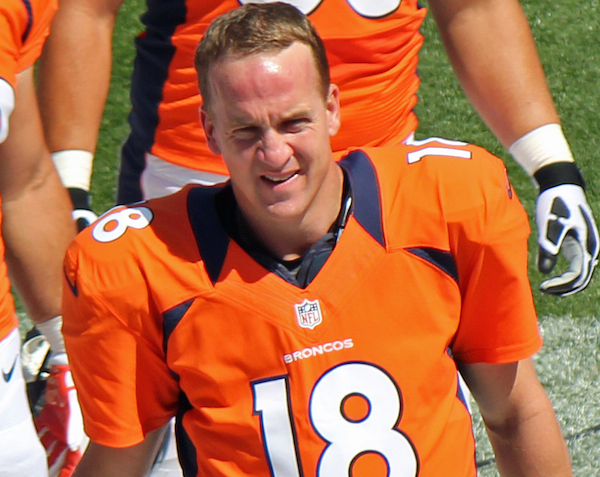

The Super Bowl is one of the biggest sporting events in the world. It’s certainly the biggest sporting event in the United States. This year, the game is between the Denver Broncos and Carolina Panthers and will be held at 6:30 on Sunday, February 7 and televised on CBS. Watching any football game is more fun if you understand who the key characters are and what compelling plots and sub-plots there are. It also helps to know some of the basic rules of how football works. Dear Sports Fan is here to help you with both! For learning the basics of football, start with Football 101 and work up to Football 201. To learn about the characters and plot, read on and stay tuned for more posts throughout the week.

As is true of most American institutions, especially those with histories that go back 100 years or more, professional football has a complex, coded, and cruel history of racism. Although we have undoubtedly made giant strides toward correcting many of the racial issues in society and sports, many remain. The racial issues that remain are almost never talked about openly on television. Instead, they are referred to with a delicate coded language that you have to be on the inside of sports culture in order to catch. As surely as it is my goal on Dear Sports Fan to help people understand the basic terms of football, it is my responsibility to try to help sports outsiders understand the racist history and coded language of football. Super Bowl 50 provides a great opportunity to do this, particularly through the character of Carolina Panthers quarterback Cam Newton.

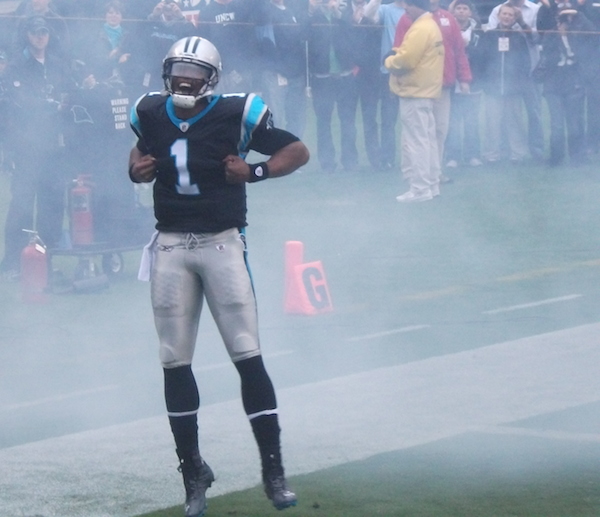

In my previews of the last two Carolina Panthers playoff games, here’s how I’ve described Newton: “Quarterback Cam Newton is, and always has been a lightning rod for controversy. In college, he won a national championship with Auburn, and it was an even more open secret than with most high-profile college players that he had taken fairly large sums of money under the table for playing there. In the NFL, he’s been the subject of years of criticism for being too self-impressed, too brash, both criticisms that have suspiciously racial overtones. From a strictly football standpoint, he’s been an amazing success. He’s a combination of one of the top ten pure passers in the league with a top ten running back in a single body. Newton ran for over 600 yards and 10 touchdowns this season. This makes him an unusual double-threat for opposing defenses to fret about, especially when the Panthers get close to the goal line.”

For a long time in football, even after the sport had been integrated, African-Americans were barred from playing quarterback either directly or because of unconscious bias on the part of coaches who thought quarterbacks required too much intelligence or leadership to be played well by Black athletes, who they felt were lacking in those qualities. Black players were pointed toward positions like running back, wide receiver, and any defensive role, all of which were thought to reward people with great “athleticism” or “natural talent” — both phrases used to describe African-Americans. The “athleticism” stereotype claims that African-Americans were either bred by slave-owners to be more physical than White people or are somehow genetically superior to White people (which offers an excuse to believe that the reverse could be true morally or intellectually). The “natural talent” descriptor is a subtle way of building on that idea while adding the insulting suggestion that Black athletes don’t practice, train, and study their craft as much as White athletes (who are often described as having “great motors” or as being “hard workers.”

As the cultural ban on African-American quarterbacks receded in the 1990s and 2000s, it was replaced by a new bias. Black people could be quarterbacks, but they wouldn’t do it the same way as White people had. The phrase “Black Quarterback” became synonymous with “running” or “scrambling” quarterback — a player who leveraged his athletic ability and improvisational skill to threaten a defense through passing or by running with the ball himself. Never mind that there had been plenty of White quarterbacks who had played with this style before, and some examples of African-American quarterbacks who did not play with this style (although most African-American quarterbacks have been scramblers… perhaps another example of bias in coaches who accepted Black quarterbacks only if they conformed to a single idea of how someone who looked like one way would play the position). The term “Black quarterback” also offered another way of attaching a derogatory association to African-Americans, because the accepted wisdom is that a scrambling quarterback will generally have a shorter and less successful career than a pocket passing quarterback.

Finally, in the 2010s, the NFL and football culture is beginning to accept that African-American quarterbacks can play the position with all different approaches. What remains of the bias, however, is a desire to control or judge Black quarterbacks on how their non football-related behavior on and off the field. Although the culture seems to be accepting that a Black quarterback may stand in the pocket and pass the ball instead of running himself, it’s still slow to accept that player’s personal expression through his clothing, public comments, and on-field behavior including celebrating with or remonstrating his teammates. This, then, is the final frontier for racial acceptance in football.

Cam Newton is, as I wrote before, almost the perfect lightning rod for all of this racially loaded history and emotion. He is a traditional so-called “Black quarterback” because of his power and proficiency running with the ball, but his equal success throwing the ball defies expectations. He also refuses to adhere to traditional notions of how a quarterback is expected to speak and behave. As a rookie, he famously stated that he wanted to be, not just a football player, but an “entertainer and icon.” This broke an unwritten rule, enforced more stringently, I would imagine, for African-Americans than White players, that players should focus only and obsessively on their sport. (Never mind that his opposite in this game, Peyton Manning, has hosted Saturday Night Live a half-dozen times and seems to be on every third television commercial.) On the field, he celebrates openly, joyously, and if you listen to some of his critics, notoriously. Again, this breach in football-decorum seems to be more noticed and criticized when a Black player breaches it than when a White one does.

If you’re looking for a positive ending to all of this, there is one. In sports, winning seems to wipe away almost all biases. Just by making the Super Bowl, Cam Newton has already silenced and even turned most of his critics. What’s more, the Panthers are favored to win this game, so there’s a good chance that Newton’s impact on race in football is just getting started.