Dear Sports Fan,

Why do people like fencing? I went to my cousin’s fencing tournament and I couldn’t follow it at all. It looked like people just jumping at each other and arbitrarily scoring. What am I missing?

Thanks,

Frances

— — —

Dear Frances,

Good for you for supporting your cousin, even if it was hard to tell what was going on and to enjoy the fencing tournament. You’re absolutely right that fencing can be bewildering to watch if you don’t know what’s going on or are far away. That said, there are lots of good answers to your question of “why do people like fencing?” Here are just a few:

- Fencing is the Paleo of sports — what is more “natural” than fencing? I suppose boxing or any of the track and field events are on the same level with fencing, but it doesn’t get much more instinctive than grabbing a long object and trying to hit the other gal before she hits you. There’s an appeal to sports like fencing that abstract a real-world (and in the case of fencing, absolutely vital) activity and puts it into a sports context. If you care to learn more than you ever thought you’d know about the history of fencing while seriously enjoying yourself, Richard Cohen’s By the Sword: A History of Gladiators, Musketeers, Samurai, Swashbucklers, and Olympic Champions is your best bet.

- So many awesome cultural parallels — If there was ever a sport to capture the imagination of children and adults alike, it would be fencing. In our days of seemingly constant, low-grade but disturbing armed conflict, there’s something romantic about the days when combat was done face to face between people armed with swords. Not that war was ever actually romantic in any way but it certainly seems that way from the way it shows up in our culture. From the lightly satiric The Princess Bride

to the many versions of Robin Hood (I grew up with Errol Flynn’s version and, of course, the comedy, Robin Hood: Men In Tights) to one of the consensus top ten movies ever filmed, Seven Samurai, to the modern classic of revenge, Kill Bill, sword-fighting has been at the center of many of our favorite movies. Even our best science fiction movies like Star Wars take fencing into the future to grab viewers’ attention. In terms of books, there’s almost an entire genre (fantasy) that leans on the appeal of fencing to draw its audience in. I’ve recently enjoyed a new epic series called the Mongoliad that’s chock full of sword fighting and describes in great detail different styles of fencing from Northern Europe to the Mediterranean to Mongolia. LARPing or Live Action Role Playing is an increasingly popular activity for people interested in sword fighting. None of these things are fencing but any of them could be a reason for picking up the sport and giving it a try.

- Fencing is incredibly fast and graceful — As you mentioned in your question, it’s sometimes hard to see what’s happening because fencers are so fast and it’s definitely hard to tell how precise, measured, and graceful their movements are because great fencers package seven distinct motions in the time it takes most of us to think about getting off the couch. A practiced fencing fan, likeRay Glickman, the grandfather of top U.S. Junior Boy’s fencer Ethan Mullennix, can learn to appreciate fencing in person. “It’s just beautiful to watch. They move like ballet dancers,” Glickman said to Mike Kepka for his article on Mullennix in SFGate.com. For the rest of us, luckily, we can watch videos of fencing in slow motion like this amazing one

http://youtu.be/Z86tpjRaiK8?t=1m36s - It’s an amazing workout — I did a couple weeks of fencing camp when I was a kid, so I can personally attest to this benefit of fencing. It may not look like it would be as much of a workout as some other sports, but the main challenge is not one that’s easy to see if you’re not looking for it. Virtually every move in fencing, from the start of a bout to the end, is done in a full-on deep knee bend position. It’s like playing a sport while doing squats. After just a minute or two of fencing, your quads begin to burn and they don’t stop. If you’ve got bad knees or are trying to protect yourself from ever having bad knees, fencing is the perfect sport for you. According to www.findthebest.com, you can burn 430 calories for 150 lb person in one hour of fencing.

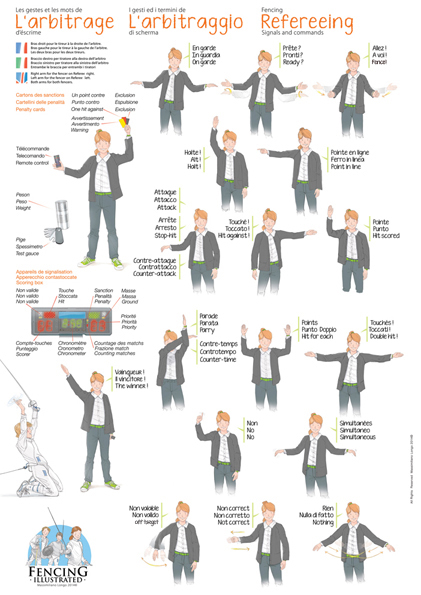

- Technicalities and technology — One of the common themes that runs through enjoyment of sport is understanding and enjoying the technicalities of an activity. Fencing has an enormous number of technicalities! First of all, there are three types of fencing, each which has a different weapons and a different set of rules about where you are allowed to hit your opponent. Even more delightfully technical are the right-of-way rules that dictate who gets the point if the two fencers hit each other at exactly the same time. The action is so fast and the rules so precise that most guides to watching fencing, like this one from Crimson Blades fencing academy, suggest watching the referee to see what has happened. Even this takes some work to learn how to interpret the referee’s hand signals as you can see in this awesome poster:

This wonderful illustration of the referee signals in fencing (one wonders if, in action, they look just a little like this,) comes from fencing instructor and author Massimiliano Longo who is currently raising money for a US and UK version of his wonderful illustrated guide to fencing for children. Please give his Indiegogo page a look and think about helping to fund it. I donated today!

So, there you have it — five answers to the question, “Why do people like fencing?” I hope these give you a reason to go back to your cousin’s next fencing tournament or even think about starting to fence yourself! If you’re interested, U.S. Fencing is a good resource for finding a fencing club near you.

Thanks for reading,

Ezra Fischer