Dear Sports Fan,

I know we’ve had presidents who were actors (well, at least one) and presidents who were generals, and lots who were lawyers. Have we had presidents who were athletes?

Thanks,

Richard

Dear Richard,

We have had presidents who were athletes. Off the top of my head, I know that Gerald Ford played center for a big-time college football team, which makes it doubly funny that his Saturday Night Live parody was almost completely based on his clumsiness. Barack Obama’s skill on the basketball court is probably a little overstated, but its importance to him cannot be. I believe Teddy Roosevelt overcame a fairly severe asthma condition to become an avid outdoorsman and big game hunter. And we all know how much exercise he got on the stairs in Brooklyn. I don’t think George W. Bush played a sport at the collegiate level, but the first pitch strike he threw out in the World Series after 9/11 was a chill-inducing presidential athletic moment in my memory. You deserve an answer with a little more weight though, so I researched the topic. Here is what I found.

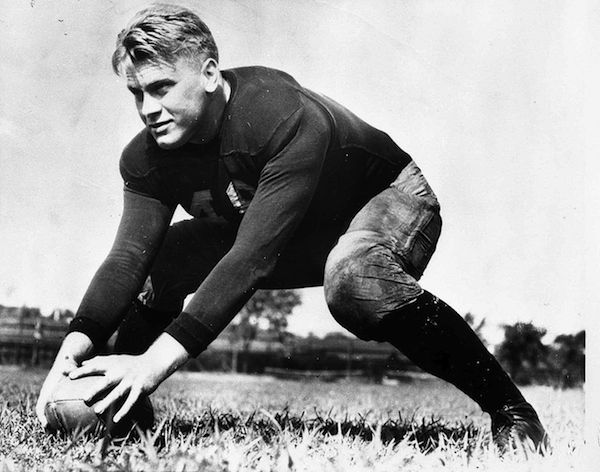

I’ll stick with my original answer. Gerald Ford was one of our most athletic presidents. He not only played center for the University of Michigan, but he also played linebacker and long snapper. In 1932 and 1933 his University of Michigan Team was undefeated and won the national championship. Even more impressively, in 1934, Ford briefly quit the team in protest for the racially motivated benching of his best friend on the team, an African-American running back named Willis Ward.

George H. W. Bush also played college sports. He was first baseman and captain of the Yale baseball team and played in the first two College World Series ever held. Oddly enough, he was also a member of the Yale cheerleading squad, something his father, and his son, future president George W. Bush, also did at Yale.

Dwight D. Eisenhower has a compelling athletic back story. While attending the U.S. military academy at West Point, he played football, starting at running back and linebacker in 1912. He either made or missed a tackle on the legendary Jim Thorpe, (sources seem to disagree, but even today, a tackle is a highly subjective statistic, so we’ll give it to him.) He also injured his knee badly enough to need to give up football… although Wikipedia claims he then moved on to “fencing and gymnastics,” which are both highly knee-dependent sports, so who knows. There’s also the mysterious matter of the Eisenhower baseball controversy. In the summer before he went the West Point, he may or may not have played semi-professional baseball under the pseudonym, “Wilson.” If he did, then he may be our only president who personally violated the NCAA ban on paying “student athletes.”

Many other presidents have been athletes. George Washington apparently had a hell of an arm. John F. Kennedy was on the swimming team at Harvard, an avocation which may have saved his life when his patrol boat went down in the Pacific Ocean during World War II. But my favorite piece of presidential athletic trivia that I picked up was from this article on Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln was not only a champion wrestler who took on all comers and a fair number of wagers during his life, but he was also an excellent handball player! In a moment that parallels and foreshadows President Obama’s tradition of playing basketball on election days by almost 150 years, Lincoln played handball (and was injured slightly) while waiting for news of the 1860 Presidential nominating convention.

Thanks for reading,

Ezra