All About Boxing

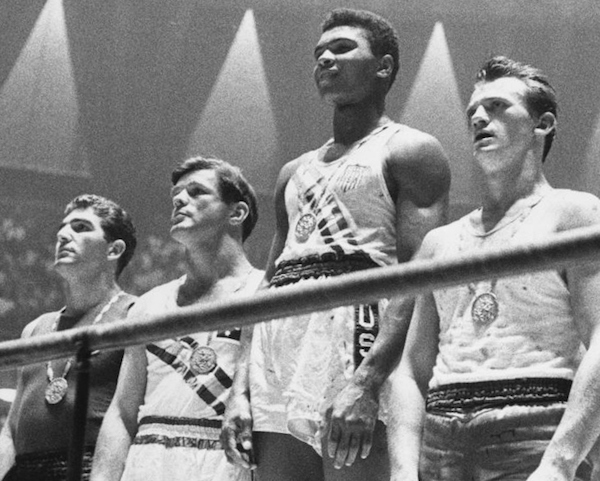

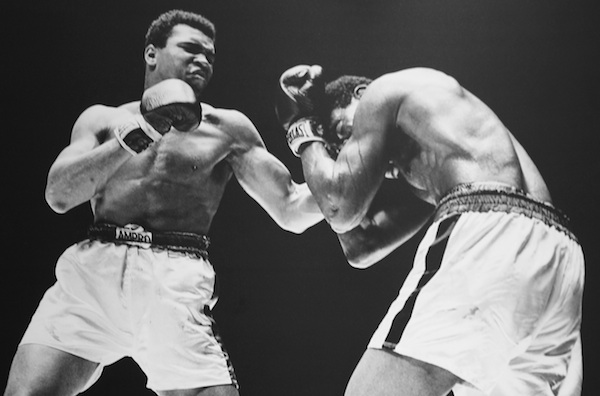

The death of Muhammad Ali provided a reminder of a time when Olympic boxing could launch a victorious athlete into international stardom. Since the 1960 Olympics in Rome, when Ali won the light heavyweight gold medal, boxing has gone through many changes. As its popularity waxed, the importance of the amateur-only Olympics lessened. Then, thanks largely to a disorganized and corrupt galaxy of competing promoters, leagues, and organizing bodies, professional boxing itself began to wane in popularity. These days, only a fight once every two years or so gets the wider public excited. From an American perspective particularly, things have been uninspiring over the last few decades. We haven’t had a star to root for. In this great boxing vacuum, it’s just possible that the Olympics once again become a place where stars can be born.

How Does Boxing Work?

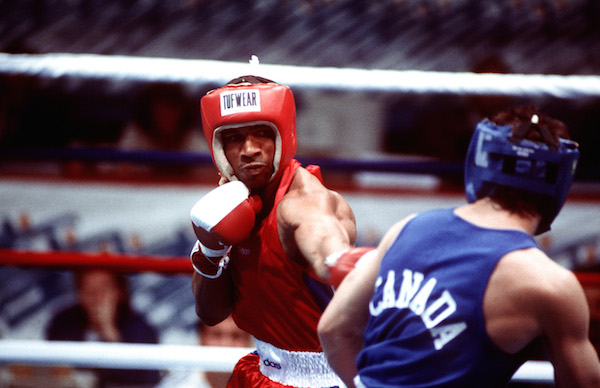

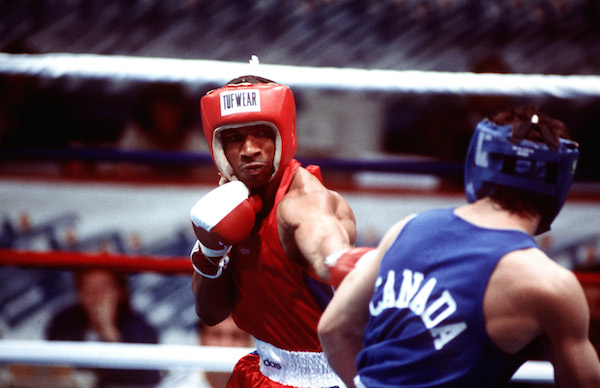

Olympic boxing in 2016 will look a little different from how it has in the past. Between the 2012 Olympics and 2016, a number of changes were made, most of them shifting the Olmypics toward professional boxing. First, professionals are now allowed to compete. Second, for men, the soft helmets that had long been required at the Olympics have been removed. This is an interesting move — it follows increasing understanding of how concussive and subconcussive blows damage the brain — and it means that fans can see their boxing heros more clearly as they fight. Unlike professional boxing, bouts in the Olympics are relatively short, but boxers must fight multiple times in a short period. The headgear, although it did not protect against brain injury, did help boxers avoid cuts and swelling. Fighting without a helmet when you know you have to fight again soon means that fighters will need to find ways to avoid getting cut. A fighter who can fight through a cut to win a bout may still find him or herself having to withdraw from the competition before the next fight. Another change is the judging system — five judges score each round of each fight, with the winner of the round getting a score of 10 and the loser a score between six and nine depending on how close it was. At the end of the bout, a computer randomly choses three of the five judges whose scores are tallied to determine a winner.

Why do People Like Watching Boxing?

In my article about why people like boxing, I identified four key reasons: boxing is elemental, boxing is highly technical, boxing tests athletes to their limit, and boxing has great stories. In a competition full of elemental sports (run fast, swim fast, lift the heaviest thing, etc.) boxing is right up there in its elemental nature. Two fighters step into a square area (confusingly called a ring) and punch each other. Elemental does not mean angry though — you almost never see fighters lose their tempers. Part of what makes a boxer good is her or his ability to think calmly and analytically even when they’re getting punched in the head. Although the shorter Olympic boxing format reduces the drama of watching two boxer push themselves to the limit of their endurance in a single bout, the cumulative effect of fighting many opponents in a short period will make the eventual champion extraordinarily impressive. Will their be great stories in this year’s Olympic boxing? Only time will tell.

Check out some highlights from the 2012 Olympics:

What are the different events?

Boxing is divided into weight-based categories. This is like a quick first pass at making sure bouts are reasonably even. There are ten men’s weight classes ranging from light flyweight (less than 49 kg or 108 lbs) to super heavyweight (over 91kg or 200 lbs) and three women’s classes: flyweight (less than 51 kg or 112 lbs), lightweight (less than 60 kg or 132 lbs), and middleweight (over 75 kg or 165 lbs).

How Dangerous is Boxing?

There’s actually very little risk in Olympic boxing of dramatic sudden injury. Thanks to the short format, knockouts (when one boxer knocks the other boxer unconscious or otherwise unable to continue fighting) are very rare. On the other hand, if you consider long term brain injury to be a danger, then boxing is pretty the most dangerous sport imaginable. Even without the headgear on the men’s side, the light, cushioned gloves mean fighters can take more damaging punches without losing consciousness, causing more damage over time. Boxing is not safe.

What’s the State of Gender Equality in Boxing?

In addition to their being many more weight classes (and therefore gold medals and competitors) for men than women, the rules are also different in curious ways. As mentioned earlier, men are no longer using cushioned headgear because going without is safer in the long-run. So, why are women still wearing them? Surely it’s because some chauvinist somewhere thinks either that women can’t handle being cut or that no one would enjoy watching them get cut. That’s absurd. Men’s bouts are also a minute longer (nine instead of eight) and cut up into longer rounds of three minutes each instead of two.

Links!

Bookmark the full Olympics schedule from NBC. Boxing is from Saturday, August 6 to Sunday, August 21.

Read more about diving on the official Rio Olympics site.