Dear Sports Fan,

One of the things that I find confusing about sports is the unique technical language that goes with each sport and which sports fans seem to all know without needing to learn! For instance, I know that the start of a football game is called the kick off but I’m not sure about other sports. What are the terms for starting a game in different sports?

Thanks,

Lauren

Dear Lauren,

There are a lot of different terms for when a game starts in different sports. The good thing is that you can almost always get by with a generic term and still fit in, even amongst the craziest of sports fans. For instance, if you’re running late to a game and you’re encouraging a friend to walk faster, you could say “Come on! I don’t want to miss the start of the game.” No matter what sport you’re headed to, that’s a reasonable thing to say. If you do want to learn the specific terms for each sport, here’s a list of them with a little detail on what happens at the start of each one.

American Football begins with the kick off

At the start of an American Football game, one team kicks the ball off to the other. The ball is placed on the 35 yard-line of the team that is kicking off. Their team’s kicker kicks the ball down the field while his teammates sprint down it, trying to make sure that they are in position to stop any return. The other team can catch the ball and run down the field with it. Wherever they run to before they’re tackled is where they start their offensive possession with the ball. If the kick goes out-of-bounds, the receiving team gets the ball on their 40 yard line. If the kick goes out the back of the end-zone or if the receiving team catches it in the end-zone and decides to stay there, the receiving team gets the ball on their 20 yard line.

Basketball starts with the tip or tip-off or opening tip

The first event in a basketball is a jump ball. In a jump ball, the referee throws the ball straight up between two players and as soon as it reaches its apex, both players try to tap the ball into the hands of one of their teammates. Whichever team gets control of the ball first gets the first offensive possession of the game. Jump balls used to be much more common than they are today. Early in basketball’s history, jump balls were used after almost every stoppage and skill at corralling them was important. These days, they happen at the start of the game and not too many other times, so basketball players don’t practice them that much.

Soccer starts with a kick off

Soccer games start at the center of the field with two players from one team standing right near the ball and no one else in the center circle. The game begins when one of the two players kicks the ball and it rolls forward. The player that kicked it initially can not be the next player to touch the ball, so frequently her teammate steps up and then kicks it backwards to another teammate. The ball does need to roll forward though to begin the game. Although it’s rarely attempted and even more rarely successful, a goal can be scored directly from the kick off, so if you feel like taking a shot, go for it!

Baseball begins with the first pitch

This one is a little confusing because there is a ceremonial first pitch and an actual first pitch and they are both referred to with the same phrase. Before a baseball game begins, there’s usually some celebrity or honoree who goes up to the pitching mound and throws a ceremonial first pitch to the catcher. Although it’s just for show, first pitches of this type can be very important. Politicians, in particular, are believed to be judged by their ability to throw out a good first pitch. Whatever you think about President George W. Bush, you have to admire his first pitch in the World Series following the terrorist attacks of 9/11. President Obama didn’t fare quite as well although you’ve got to appreciate his trolling of the home town Washington Nationals fans. It may seem idiotic to compare the two presidents on something as prosaic as throwing a baseball, but that doesn’t stop people from doing it. Just check out this somewhat bizarre video. Anyhow, after the ceremonial first pitch, there’s usually a commercial break (in person, this is just empty time with everyone standing around) and then the teams come on the field and the starting pitcher throws the real first pitch to get things started.

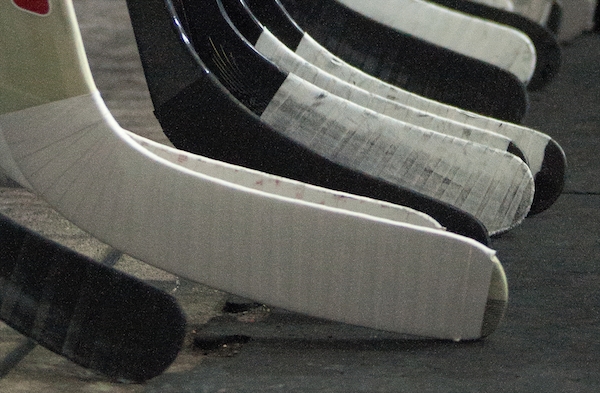

Hockey begins with the puck drop

Now that we’re nearing the end of our list, we can begin building on what we’ve already explained. The start of a hockey game shares some elements with baseball and some with basketball. Like baseball, there is a ceremonial puck drop with an honored guest emulating the act that’s going to start the game in earnest in a few minutes. Like basketball, the first act involves the referee putting the puck (ball in basketball) into play evenly between two players who fight to gain possession. In hockey, the drops the puck instead of throwing it up in the air and the action is called a face off not a jump ball. In both cases though, the term that describes the start of play is a description of what happens (in basketball the players try to tip the ball, in hockey the referee drops the puck). In either case, referring to the start of the game with the technical term – jump ball or face off – would also be acceptable.

Car racing starts with the green flag

Car racing comes in many different forms involving different types of cars on different courses with different rules. One thing that’s constant in almost all forms of racing is a simple set of flags that convey meaning to the drivers. These flags come from a time before every race car driver had a speaker in his ear and a microphone in front of her mouth. The signal for the start of the race is a solid green flag. It’s also used during the race to signal the end of a caution period (yellow flag) when the drivers must slow down. The end of the race is symbolized by a white and black checkered flag.

There we go — five terms for the start of six different sports. I hope that helps to assuage your fitting in jitters. There are lots of other sports, each with their own technical languages. If you’re a fan of one of those sports, send me a note at dearsportsfan@gmail.com with your sport’s term for the start of the game.

Thanks for the question,

Ezra Fischer