Dear Sports Fan,

What is a conference in sports? What makes a conference a conference? And why is it called a conference?

Thanks,

Erik

— — —

Dear Erik,

Thanks for your question. A conference is a collection of teams that play more against each other than they do against the other teams in their sport. As you’ll see, conferences have various histories and meanings in different sports. In some sports conferences are defined geographically. In some they are the remnants of history. In some sports the conferences are actually pseudo competitive bodies themselves and in other sports they are cooperating divisions within a single organization. Conferences vary in importance and independence from sport to sport. Before we get into the differences, let’s start with some general truths about conferences that apply across (almost) all sports.

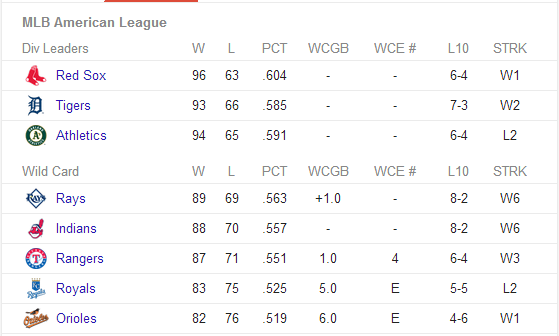

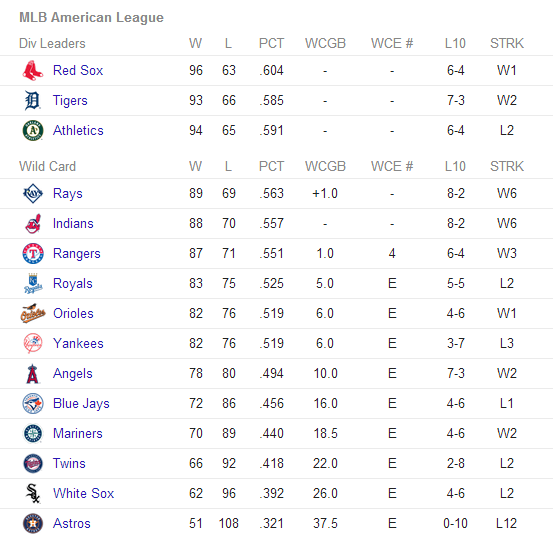

Teams within a conference play more games against each other than against the other teams in their sport. It varies by league and by sport. In the NHL, for example, teams play at least three times per season against every other team in their conference but only twice against teams from the other conference. In Major League Baseball teams only play 20 of 162 games against teams from the other conference.

Conferences crown conference champions in all sports. In many leagues like the NFL, NBA, and MLB, playoff brackets are organized by conference. Teams in the AFC (one of the NFL conferences) only play teams from the AFC in the playoffs until the Super Bowl. So, the conference champion is basically the winner of the semi-final game. In other sports, mostly college sports, the conferences only really have meaning during the regular season, so conferences have different ways of deciding a champion. Depending on the sport and conference, there may be a conference tournament at the end of the regular season or a single championship game between the two teams with the best records in the conference. In some conferences, like Ivy League basketball, the champion is just the team with the best record in games against other teams in the Ivy League.

What Sports Have Geographically Defined Conferences?

A geographic division of teams is perhaps the most sensible way of defining a conference. Since teams within a conference play more games against each other than against teams outside of their conference, organizing geographically saves money, time, and wear and tear on the players by reducing the overall travel time during a season. The NBA and NHL are organized in this way. Both leagues have an Eastern and a Western Conference and both stay reasonably true to geographic accuracy. The NBA has a couple borderline assignments with Memphis and New Orleans in the West and Chicago and Milwaukee in the East. The NHL recently realigned its conferences, in part to fix some long-standing issues with geography like Detroit being in the West. Geographic conferences seem logical because they simplify operations for the teams within them. Many college conferences began geographically but as we’ll see later, that’s no longer their defining characteristic or driving force.

What Sports Have Historically Defined Conferences?

It’s easy to think about the sporting landscape as a set of neat monopolies. The NFL rules football, the NBA, basketball, the MLB, baseball, and the NHL, hockey. It wasn’t always that simple. Most of these professional leagues are the product of intense competition between leagues and only became supreme after either beating or joining their rival. The NFL was formed by the merger between two competitive leagues, the traditional NFC and the upstart AFC. The NBA beat out its biggest rival, the ABA, in 1976 but took many ideas from it, like the three-point line but alas not the famous ABA multi-colored ball. Believe it or not, Major League Baseball was not a single entity until 2000! Before then its two conferences (still called “leagues” because of their history as separate entities but pretty much, they are conferences,) the National League and the American League were independent entities.

Two leagues, Major League Baseball and the National Football League continue to have conferences defined by their competitive history. In baseball, the American League and National League each have teams across the entire country, often even in the same city like the New York Yankees (AL) and Mets (NL), Chicago with its White Sox (AL) and Cubs (NL) and Los Angeles/Anaheim with the Angels (AL) and Dodgers (NL). The NFL has similarly kept its historic leagues, the AFC or American Football Conference and NFC or National Football Conference. Each NFL Conference is broken up into three geographic divisions, East, Central, and West, but they all play more against the teams in their conference, even far away, than the teams close by but in the other conference. In the NFL the two conferences play under exactly the same rules but in baseball there are still some major historic differences in how the game is played, most significantly that pitchers have to also bat in the National League but are allowed to be replaced by a designated hitter in the American League.

What Sports Have Conferences that are Competitive?

So far we’ve looked at geographic and historically defined conferences. It’s clear that geographic conferences don’t compete against each other — they are part of the same entity. You can imagine that because of their history, the conferences in the NFL and MLB may be a little competitive with each other, like brothers or sisters. There are still some conferences though where competition against other conferences is their key driving force. These conferences are largely found in college sports.

Most college conferences have geographic names — the Big East, the South-Eastern Conference (SEC), the Pacific Athletic Conference (PAC 12), the Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC), the Sun Belt, and the Mountain West. When they formed, they formed for all the reasons we discussed above in the geographic section but also to take advantage of financial arrangements that could only be made together, most importantly television contracts. As the money has gotten bigger, especially in college football, the competition between conferences for the best teams and the most lucrative contracts has become incredibly intense. In recent years, you’ve seen conferences poach teams from one another in a race to provide television viewers with the most competitive leagues to follow and therefore generate gobs of profit. This scattered the geographic nature of these conferences so that a map showing which teams are in which conferences now looks like a patchwork quilt.

Like it did with the ABA and NBA, the NFC and AFC, and the NL and AL, my guess is that this competition between conferences in college sports will resolve itself into some more stable league form. No one knows when this will happen but my guess is that it will be in the next ten or fifteen years. I guess we’ll have to stay tuned.

Thanks for asking about conferences,

Ezra Fischer