Dear Sports Fan,

What is a snap in football? I hear it all the time in what sounds like many different contexts. Can you explain them all?

Thanks,

Ollie

— — —

Dear Ollie,

You’re right, there are a lot of different uses of the word snap in football. There’s a snap count, there’s a person on a football team called the “long snapper,” and a snap can refer to the act of snapping or the moment of the snap. In this post, we’ll go through them all and connect them to other elements of football. Finally, we’ll ask why it’s called a snap and what it tells us about football.

The Act of Snapping a Football

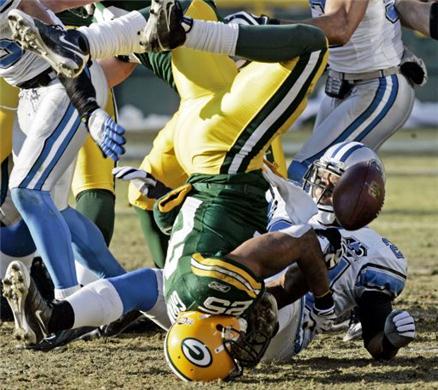

When a football play begins, the ball is motionless on the ground, positioned on an imaginary line which stretches from side-line to side-line, called the line of scrimmage. One player grabs the ball with his hand and moves it backwards between his legs to another player. That action is called the snap. The player who performs the act of snapping is the center. There are two main kinds of snaps, referred to by the position of the quarterback. A quarterback is either “under center” to receive the snap or “in the shotgun.” With a quarterback under center (right behind the center, so close that he rests one hand on the under-side of the center’s butt,) the center quickly hands him the ball through his legs. When a quarterback is in the shotgun formation, he is a between five and seven yards behind the quarterback. Snapping the football in this formation is a more challenging task — it requires spinning the football while throwing it backwards between his legs so that it flies in a straight, easy to catch spiral. You may also hear that there was a “direct snap.” This is a totally normal snap — either under center or shotgun but instead of a quarterback receiving the ball, it is a running back.

The act of snapping the football connects football to its past when, like rugby, throwing the ball forwards was not allowed. Although the majority of plays in most football games today involve throwing the ball forward, all of them begin with a backwards pass in the form of a snap. In case you’d like to learn how to snap a football, wikihow.com has a great tutorial.

Snap Count

The phrase “snap count” is pretty common but has two only tangentially related meanings. One meaning refers to any vocal cue that a quarterback gives to his own team to synchronize their movement with the snapping of the football. Because only one player on the offensive side is allowed to move at a time before the snap, a good snap count provides the offense with an advantage over the defense; it knows when to start moving and can get a head-start on the defensive players. Once in a while defensive players will mimic a quarterback’s snap count in an effort to get the offense to move at the wrong time. This is illegal and a defensive team may be penalized for “simulating the snap count.” Another meaning of the phrase snap count is the number of plays a player is a part of, usually in a single game. In this use, the snap is representative of a play and the count is just the act of counting the number of plays or snaps someone is a part of.

The Snap as a Moment

As described in the first paragraph, before a play begins, the football is motionless on the ground. The act of snapping the football begins the play and, confusingly, the moment that this happens is also called a snap. This is important because the exact moment a play begins is vital for a couple of important rules in football. Aside from the one offensive player who is allowed to move before the snap (said to be “in motion”) if any other player moves before the snap, they are offside. If a defensive player moves across the line of scrimmage and is not able to get back to his side of that line before the snap, he has encroached and will be called for a penalty. Dear Sports Fan covered both of these rules in our post on offside rules in various sports. Football, similar to basketball, has a play clock that counts down and requires a team to make an offensive play. In the NFL, the play clock is forty seconds long. If the clock runs out before the snap, there is a delay of game penalty.

The Snapping Specialist

While most snapping is done by someone playing the center position, there are some snaps that are so critical and so technically difficult that teams pay someone to perform them, even if that is almost all they can do on a football field. This player is the long snapper. He snaps the ball for punts and field goal attempts. For a punt, the long snapper needs to spiral the ball backwards to someone standing closer to 15 yards behind him than the five yards of a shotgun snap. The mechanics of a field goal snap are even more exacting because the snapper has to snap the ball in such a way that it spins exactly the right number of turns. This way the field goal holder has an easy job of placing the ball with the laces facing away from the kicker’s foot so that the kick flies true. The New York Times produced an amazing multi-media feature on this a few weeks ago.

Why is it called a snap? And what can we learn about football from it?

There doesn’t seem to be a clear consensus about why the snap is called this snap. This delights me because making up derivations runs deep in my family. Google defines snap as “a sudden, sharp cracking sound or movement” and as a secondary meaning, “in football: a quick backward movement of the ball from the ground that begins a play.” Football can be inaccessible or less pleasing to fans of other sports because it lacks the fluid motion and continuous play present in sports like soccer, basketball, and hockey. Instead of fluid play, football is characterized by quick bursts of action beginning from a standstill and creating havoc in a matter of seconds before coming to a halt. It’s no wonder then that we call the act that initiates these sudden, sharp bursts of movement a “snap.”

Thanks for the question,

Ezra Fischer