Sports are at least as big a part of raising children in this country as religion or civics. Kids spend hours every day playing sports and the way they see adults handle the everyday drama of sports helps to each them how to handle the real dramas of growing up. This week we have three stories about raising kids in and around sports. We’re going to hear from a former major league baseball player who has recently begun coaching his children’s t-ball team and from the family and friends of a young athlete who took her own life. We’ll hear about the army’s newfound devotion to women’s lacrosse and why their focused on that sport.

Confessions of a Major League T-Ball Coach

by Doug Glanville for the New York Times

Former baseball player Doug Glanville walks the line in this article. It’s tricky to write comedically about children — if the snark has even a hint of mean-spiritedness in it, the whole article will fall apart at the seams. I don’t sense snark at all, only love and appreciation for the absurd.

Base running is a little more straightforward, even though it can create moments I have never seen or imagined before in my life. The other day, we had three runners on third at the same time. After first trying to sort it out, I thought, “No big deal, let me see what happens when the hitter puts the ball in play.” So he did, and two out of the three ran home. Not bad.

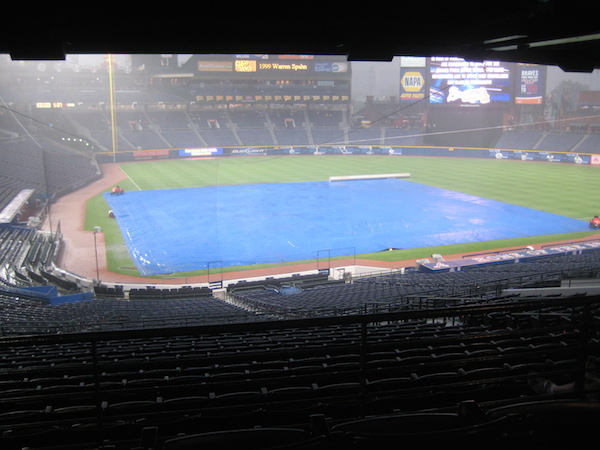

T-ball is subject to a range of delays that have nothing to do with rain. Nor do they come from pitching changes or from challenging a call with Instant Replay. No. Our catcher went off to the Port A Potty; another one of our players was shaken up after being engulfed by his own teammates (eight apparent shortstops trampled him to get a ball hit near the pitcher’s mound); a couple of other players found the joy in knocking each other’s hats off at second base — until they found themselves disoriented in the evil and boring outfield.

Why Does the Army Care so Much About Women’s Lacrosse?

by Jane McManus for ESPNW

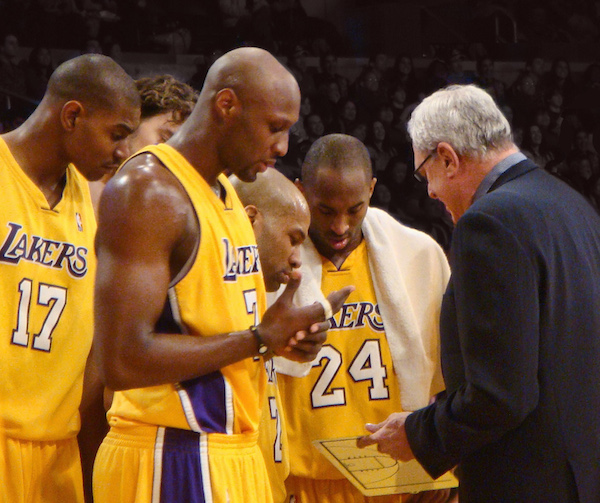

The image you might have in your mind of women’s lacrosse is that of a genteel sport played by young ladies. Don’t be tricked by the skirts that the players wear, they are ladies, but they’re the kind of ladies that will shove you to the ground and sprint over you to score a goal. That’s exactly the kind of people the army needs as they continue to open more combat positions to women.

The Army believes there is a crucial relationship between those two things — an athletic background and being a soldier. As the military prepares to allow women on the front lines of combat in 2016, there is an immediate need for strong, tough women from within the Army’s ranks. And, in a philosophy often mentioned on campus and believed by MacArthur himself, the Army believes athletes make better soldiers.

The data seems to support the basic premise held at West Point: that female athletes possess critical tools that would make them ready for the front lines of combat. Lacrosse is the next frontier for pulling good athletes to the academy

Split Image

by Kate Fagan for ESPN

This is a brutal article. It tells the story of Madison Holleran, a successful multi-sport athlete who recently died by suicide. As much as her family and friends would like there to be an answer to why and what we can do as a society to prevent other people from doing the same, there just isn’t. Depression is a nasty disease and it can strike anyone, anywhere. What follows here is some of Fagan’s writing about the impact of social media on young women’s lives. It’s not an explanation for suicide but it is something that we can improve.

Madison was beautiful, talented, successful — very nearly the epitome of what every young girl is supposed to hope she becomes. But she was also a perfectionist who struggled when she performed poorly. She was a deep thinker, someone who was aware of the image she presented to the world, and someone who often struggled with what that image conveyed about her, with how people superficially read who she was, what her life was like.

Everyone presents an edited version of life on social media. People share moments that reflect an ideal life, an ideal self… With Instagram, one thing has changed: the amount we consume of one another’s edited lives. Young women growing up on Instagram are spending a significant chunk of each day absorbing others’ filtered images while they walk through their own realities, unfiltered… She seemed acutely aware that the life she was curating online was distinctly different from the one she was actually living. Yet she could not apply that same logic when she looked at the projected lives of others.