Dear Sports Fan,

What does the stat Wins Above Replacement or WAR mean in baseball?

Thanks,

Rich

— — —

Dear Rich,

Wins Above Replacement is one of the many statistics that have either invaded or enhanced baseball over the past twenty years, depending on your perspective. It’s a single stat made up of many parts that tries to summarize the overall value of a player to the success of their team in a single number. The higher a player’s WAR number, the more they have contributed to their team’s success.

WAR is expressed as the number of wins a player’s team won thanks to their contributions as compared to what the team would have won (speculation warning) if they had been replaced by someone else. Baseball Prospectus, one of the several entities that has their own way of calculating WAR, lists Tim Keefe’s 1883 season as the best ever, during which he contributed 20.2 wins to the New York Metropolitans. If, instead of Mr. Keefe, the Metropolitans had had to scour their farm system for another right handed pitcher, this stat suggests they would have only won 34 games instead of the 54 they actually won.

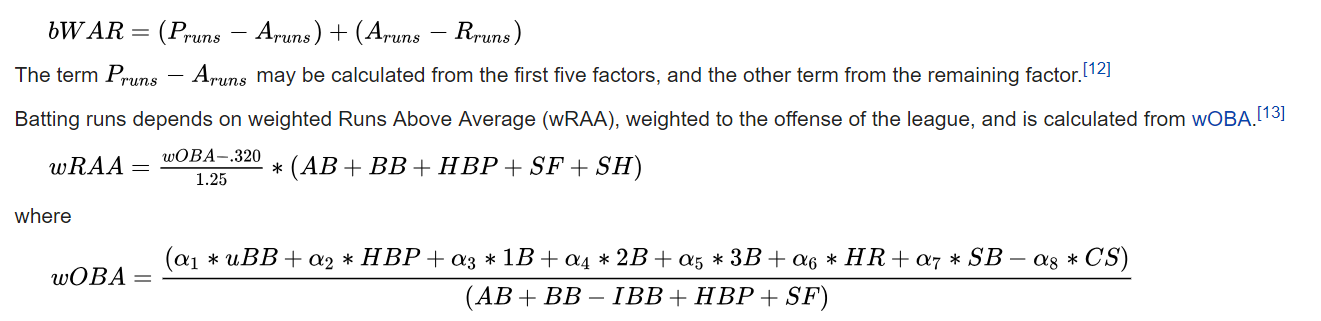

Here’s the thing about WAR: because it’s intended to be an all encompassing statistic, it’s very complicated. It encompasses a lot of stuff! This is a screenshot from the Wikipedia article on WAR:

Woah! Don’t panic though. In order to understand WAR at a basic level, we need to understand two things — what elements are scored to show whether a player is doing well or poorly and what a replacement player is and how their potential contribution is defined.

What contributes to a player’s Wins Above Replacement?

Although different groups calculate WAR using different formulas, there are some general elements that go into figuring out a player’s contributions to their team. Offensive statistics having to do with hitting and base running are used. Defensively, an everyday player’s fielding is looked at whereas all sorts of pitching statistics are available for pitchers as well as the batting statistics of opposing teams. Overarching all of this is availability – in order to contribute, you’ve got to avoid injury.

What is a replacement player and how is their contribution defined?

Here’s where WAR gets all highfaluting and counterfactual. It’s all very well to measure a player’s contribution to their team’s victories but that’s just the first letter in a three letter statistic! The AR in WAR means “above replacement.” In other words — if Old Hoss Radbourn (the second highest single-season WAR player ever) had broken his ankle before the 1884 season, how would the Providence Grays have done? This question begs another question — who would he be replaced by?

The creators of the WAR statistic believe that there is a generally available and definable level of baseball talent that we can assume would replace any player out there. Given baseball’s well established farm system, (there are 19 minor league baseball leagues with 256 teams in the Major League Baseball ecosystem) that’s probably somewhat true. A replacement-level player is defined for most WAR calculations as one who is 80% as good as the average major league baseball player. One exception to that is the catcher position, which despite (or perhaps because of) being the coolest position in the sport, has fewer players who are decent at it. For that reason, replacement-level catchers are defined as 75% of the league average catcher.

So that’s WAR or Wins Above Replacement in baseball. I find it an interesting statistic because it contains within it the terrifying truth of many professional athlete’s lives that they are eminently replaceable. It’s also sort of funny to think about extending the logic of the statistic to everyday life. “How’s the fried calamari at this place?”

“It’s great — I’d say it’s about seven YAR”

“YAR?”

“Yums Above Replacement…”

Thanks for reading,

Ezra Fischer